- Home

- Kim Newman

An English Ghost Story Page 8

An English Ghost Story Read online

Page 8

On impulse, she edged open the bottom drawer and reached inside. She found a limp length of cloth and pulled it out. A school tie, in the colours of Drearcliff Grange. She snapped it like a whip and Steven yelped.

‘I’m going to bind you fast, sir,’ she said. ‘Then we shall see if you can take punishment with as much relish as you hand it out.’

She held the tie between her fists, like a garrotte, and walked slowly across the room.

Steven laughed in terror.

* * *

On the telephone, Jordan remembered to be cool. She shrugged and pouted as expected, and was noncommittal. As soon as Rick rang off, she yowled with glee.

He was coming to the Hollow!

Next weekend. Then, everything would be perfect. Rick was going to love the place and they would explore it together. She had been holding back, not joining Tim or Mum in their expeditions, promising herself she would discover the territory alongside her boyfriend. She was saving some of the surprises to share with him.

He had no news from the city. College was over for the year. For Rick, it was over for good. He had to wait for his results. She was sure he would get the grades he needed for UWE. She did her girlfriend bit and fed him support.

Rick said he had run into Mum’s strange friend near the old flat. Mention of Veronica was like a black claw in a cream cake. Jordan called her the Wild Witch, and Dad had far worse names for her. Jordan was surprised Rick only vaguely remembered who the woman was. She must have bored him with horror stories of the Wild Witch’s malign influence. When he had tentatively said Veronica didn’t seem so bad, Jordan had seriously wanted to strangle him.

Here, at the Hollow, they were safe from wild witches.

When he was here, Rick would be safe too.

She realised she was the only one up. Tim’s bedtime was eight and Mum and Dad had taken to going to bed earlier and earlier. Jordan still wasn’t a hundred per cent keen on thinking about that, but it made a welcome change from open warfare.

She was in the Summer Room, curled on the overstuffed sofa, with the cordless phone still stuck to her sternum and a shawl wrapped around her.

Dad had spent a day hooking up their giant-screen television with satellite and other gadgets, but even Tim hadn’t watched it much. There were other things to do at the Hollow. At first, the TV, like other Naremore additions, had stood out among the furnishings that had come with the place. Now, it blended in. The television cabinet even matched the smoky-brown rosewood look of the dresser and the table.

It was a familiar shade, the dominant colour of the house.

She thought of watching a favourite film. Bye, Bye Birdie, Move Over, Darling or Charade. Other girls her age liked Tom Cruise or Leonardo DiCaprio, but her top male film stars were Cary Grant and Rock Hudson. Rick had made fun of her for her Doris Day enthusiasm, until she introduced him to mid-sixties Ann-Margret and Stella Stevens. She liked the hard, sparkly colours, the brashness and confidence even of neurotics, the brassy orchestrations of the theme songs. For his birthday, she had bought Rick a sports jacket with a fine hound’s-tooth weave. She wanted them to be like the chummy but peppery couples in the films, who constantly teased each other but were hipper and smarter than the rest. They were a team against the phonies and the squares.

Here, she didn’t need to watch the films any more. They were in her mind, in her heart.

Was it too soon to call Rick again?

It was. Pity.

She stood, shrugging out of the shawl, and walked across the room to replace the phone in its cradle. When she turned back, her shawl was still in the air, as if settled around invisible shoulders. The old thing had come with the house it was a faded white crochet with long tassels and a pleasant woolly smell.

Jordan remembered to close her mouth.

The shawl hung in the air, looking like a cartoon ghost with eyeholes and a trailing shroud.

Jordan laughed and the shawl swirled upwards in a spiral, tassels spinning, until it was a magic carpet. It rose almost to the ceiling and stretched out like a table-cloth, then gently floated downwards and draped perfectly over the back of the sofa.

She clapped, slowly.

The break with the world she had known, had almost grown up in, didn’t frighten her. Her bare feet tingled, with the beginnings of excitement. Could she conduct the ghost shawl, make it dance at the lift of a finger? She decided it would be impolite. She was too old for toys. This wasn’t a gimmick or a game – no hidden fishing line or computer imagery – but a revelation, an epiphany.

She was as comfortable with the Hollow, and whatever shared it with her family, as she was with Rick, as she had only recently become with her brother and parents, as she hoped to be with herself.

She was smiling and crying at the same time.

* * *

Tatum seemed spooked by the size of the study. She was the first person from their London life to come to the Hollow. Steven had suggested she stay over – one of the spare rooms was quite liveable now – but she wanted to drive back for a late party with her fiancé.

Steven had naturally set up shop in the study, though he was considering eventually having the hayloft converted into an office suite. He liked the idea of a workspace separate from the house. For the moment, Louise’s old lair suited him fine. Her books and papers were in boxes now. Kirsty wanted to go through them before she shared them with Wing-Godfrey’s Society. Jordan and Kirsty had gone on reading jags, scurrying through the children’s books, reporting on every Hollow reference the authoress dropped. He had put his own files into the cabinets and begun to occupy shelves with active folders.

Tatum had held the fort during the interregnum. She ran down deals that were tied up, in development or scotched. He was impressed his personal assistant didn’t blame herself for the one that had blown up. It wasn’t her fault, but it would have been like an overeager junior to think it was. No black mark against her.

During the worst of it, he could rely on Tatum. She had thrown in her lot with him and would stick to him, no matter what. Even before this absence, she had shouldered more than her share of the gruntwork. While he was preoccupied, it had been possible that the whole business would be taken away and torn to pieces. Tatum had seen them through. He had written her in for a percentage on top of her salary. Within a year or two, he would have to make her a partner to keep her aboard. She could handle the city, the face time in crowded coffee bars and the running from one meeting to another, while he sat here in the country, hooked into the world of information, processing like a human computer.

He laid out a couple of long shots for her. It was like Kirsty’s supposed trick with the tree and the standing stones. You had to stand in just one place and look just the right way to see something invisible from everywhere else. In the last week, he had managed it three times, sighting through fiscal tangles to see opportunities being born like new stars.

Tatum slipped his print-outs into her leather document case. He saw she had the scent of blood.

‘This place, Steven, it’s…’

She shook her head. Tatum had one of those thin faces, with smile brackets around her mouth, which work better than they should. She wore her hair in a severe bob that set off her purple horn-rims.

‘I know,’ he said. ‘It’s taken years off me.’

‘All this paper,’ she said, indicating the bookshelves and boxes. ‘My eyes are watering from the dust.’

‘None of us have had that.’

‘You’ve gone native.’

He laughed. ‘Listen to that quiet, Tate.’

‘It sets my teeth on edge, Steven. I’d feel exposed. You’re miles from anywhere. Anyone could come by and walk in. You’d be cut off.’

‘That doesn’t happen. Only in the city.’

Tatum and her fiancé had been mugged last year. Marco had lost two front teeth. She was understandably paranoid.

‘One more thing,’ she said, taking a folder out of her case and layi

ng it on the desk. ‘This is the last of the Oddments accounts. You’re entirely clear of the mess, but Kirsty is still in a hole. I’ve talked with the outstanding creditors. If pushed, they’ll carry her for six months. Of course, they think you’ll cover your wife if it comes to that. If they forced her into bankruptcy, they’d get pennies for pounds. You’d not be legally obliged to pay off her debt. Even as it stands, you can pay or not. It’s your decision.’

‘Can I settle now?’

‘It’s your decision, Steven. You’ve enough in the accounts, even after expenses like me, but it’d leave you stretched. I’d let it roll.’

Last year, Kirsty had started up a small business, Oddments, on the advice of the insidious Vron, selling bizarre antiques over the net. It had been unsuccessful and proved more of a money pit than anyone could have expected, culminating in several major crises and one big collapse. Tatum obviously resented the shackles Oddments clapped on the expansion of Naremore Consultancy Services. Steven, more than anyone, sympathised with her, but that trouble was past, part of the life left behind. Here, things were different and he just wanted to clean up the last of the mess.

‘Pay them off, Tate. I feel lucky.’

Tatum took that on board.

‘It’ll be done. Here are the figures. If you make out and sign the cheques, I’ll take them back with me.’

She watched as he wrote the cheques. This would take a bite out of reserves already depleted by the move. But the house down-payment had come along providentially. The new ‘things can only get better’ government had changed planning laws, which meant long-ticking investment finally paid off with an unexpected gush of green. That was the beginning of the magic, providing the family with the money to escape from London and their mire of personal problems.

‘Don’t worry,’ he told her. ‘It’s about freedom.’

Tatum took the cheques and proofread them. There was an extra among them.

‘Veronica Gorse?’ Tatum asked.

‘Kirsty made her a partner.’

‘On what investment?’

‘Not money. She was supposed to be the keen eye for treasure. She put the “odd” in Oddments.’

‘I can’t believe you’re paying her off. After everything. Gorse has no legal claim. She’s lucky you don’t start proceedings against her.’

‘It’s worth it never to have to deal with the mad creature again.’

His PA shrugged. At one point, Steven had seriously suspected the muggers who attacked Tatum and Marco were Vron’s flying monkeys. They hadn’t taken anything, just thumped and run.

With the cheque written, Steven felt another stone was removed from his cairn. He would tell Kirsty later, tactfully. It was over and done. She had new interests now.

Tatum looked around the room again and shivered inside her shoulder pads.

‘I hope this is what you really want, Steven,’ she said. ‘I really do.’

‘Oh, it is, Tate. It really really is.’

* * *

In the Hollow, Tim never missed with the catapult. He could bring down an apple with a pebble. Merits for its use within the boundaries no longer awarded. When he took position on the ditch-bank and fired over the border, aiming at a patch of marsh-grass or a gate-post a field away, the shot usually went wild. But, if he turned round and picked out a particular tile on the roof of the taller tower, just above his own bedroom window, a tile he knew was there but couldn’t see from this far away, he could clip it dead centre and check later to see the rough chip raised by the impact of the stone.

He called his catapult the U-Dub, for UW. Ultimate Weapon.

He did not fire at birds or squirrels or even insects. That, he knew, was not in the rules of engagement. The U-Dub was not a first-strike weapon. It was for defence. If a bird came at him with claws and beak out for his eyes, it would be a go to put a stone into it. But the birds of the Hollow weren’t hostiles.

Still, he felt safer with a strong defence capability.

* * *

They sat, all four Naremores, at the long table, empty plates pushed away. Kirsty plunged the cafetiere and poured out cups of coffee, half and half with warm milk for Tim, midnight black for the rest of them. Jordan took a chocolate biscuit with hers. Six months ago, that would have been a miracle on a par with Weezie’s chest of drawers. It was magic hour, the sun nearly down but the sky still light. Shadows took a long time to gather in the Summer Room.

For minutes, no one said anything. The family were together, just enjoying that.

Finally, Tim asked, ‘Is the Hollow haunted?’

It was the first time any of them had used the word out loud.

Jordan looked eagerly at Kirsty and Steven. She had something to say, but didn’t want to go first.

Kirsty knew it was time to talk.

‘Yes, my darling,’ she said. ‘I think it is.’

‘Then why aren’t I frightened?’

That was the question.

‘I don’t think the Hollow is haunted that way,’ said Steven. ‘The mystery collection is enough to convince anyone this is no ordinary house, but it’s not like haunted houses in books and films. Those are bad places, where terrible things happened. You know, built on a cursed Indian burial ground, an unavenged murder victim walled up in the cellar. If there are ghosts here, they aren’t haunting us. It’s as if they’re sharing. Is there an opposite of haunted?’

‘Un-haunted?’ suggested Jordan. ‘Blessed?’

‘What about charmed?’ ventured Kirsty.

Steven was taken with that.

‘Yes, Tim… Mum’s right. This is a charmed house, a happy house. Good things have happened here and they linger like warmth. It’s in the air, like that silence after a concert, just before the applause starts.’

Kirsty drank her coffee. The grind brought here with other half-used jars and tins tasted different. That could be the water, of course. At the Hollow, they didn’t need to filter. She had stopped taking sugar in tea and coffee.

‘Do we want to talk about the magic,’ she began, hesitantly, ‘or are we afraid that if we do, it’ll go away?’

‘Magic?’ queried Steven.

‘Yes, magic,’ Jordan was eager to confirm it. ‘Things moving, things appearing. Presences.’

‘Are they what’s behind the mystery collection?’ asked Steven. ‘Ghosts?’

‘Not exactly, or not just,’ said Jordan.

‘The IP are friendlies,’ said Tim. ‘They extend full cooperation.’

‘You’ve seen them, Tim?’

‘You don’t see them, Dad. If you saw them, they wouldn’t be them.’

Kirsty thought about it.

‘I haven’t seen anything either, but I’ve been given things. In a way I can’t explain.’ She was wearing a bracelet from the bottom drawer. ‘And I’ve felt it. We’ve all felt it. Even you, Steven.’

Her husband took her hand and squeezed her fingers. He did not think she was mad. Another miracle.

‘I’ve seen something like a ghost,’ said Jordan.

Kirsty was surprised. She had never suspected.

Tim raised his arms and went ‘woooo-wooooo’. Everyone laughed, including Jordan.

‘Yes, that sort of ghost. A floating white thing. The shawl on the sofa, moving by itself. Dancing.’

‘I haven’t seen anything like that,’ said Steven. ‘I must have angered the spirits or something.’

‘I don’t think so, Dad,’ said Jordan. ‘It’s different for each of us, but it’s different again for all of us together.’

‘So who is it?’ Steven asked. ‘Louise?’

‘More like Weezie,’ said Kirsty.

‘Didn’t Miss Teazle die only last year?’ asked Jordan. ‘It’s older than that. I think the Hollow has been this way for a long, long time. It’s in the ground as well as the house, in the trees and the streams.’

‘Maybe we’re on top of an Arthurian burial ground?’

‘I’m not sure it’s to do

with the dead.’

Steven was puzzled by Jordan’s statement. ‘Ghosts are the dead, surely? Spirits left behind, business left undone. They avenge their murders or haunt their heirs.’

‘Those would be unhappy ghosts, Dad.’

Kirsty had a thought. ‘In the Weezie books, the little girl is friends with ghosts. There’s a grisly ghost in the first one – no, a gloomy ghost – which is like your idea of a ghost, the “woooo woooo” misery and chain-rattling ghost. But she meets it, makes friends with it, and it changes. I think Louise turned her own experience into a story.’

‘Cashing in?’ laughed Steven. ‘Maybe we should too? Have haunted holidays.’

‘No, dear,’ Kirsty said, serious. ‘Louise wasn’t like that. I think she was like the house. She wanted to share.’

‘Well, thank you, Weezie,’ said Steven, raising his coffee cup. ‘And thank you too, whoever or whatever you are. Thank you, ah, for having us.’

Kirsty lifted her cup too. And Jordan, and Tim.

A delicious shiver ran through her, and she knew her family shared it. It wasn’t like a wind. The window-panes didn’t rattle and magazine pages didn’t riffle. It was warm and cool at once, like a caress.

‘That was, um, enlightening,’ said Steven.

The red glow of sunset was splashed across every pane of the picture windows, bathing the Summer Room in petal-pink light. The windows formed a giant screen. Images swirled in the panes, turning the wall into living stained glass. Kirsty recognised the colours of the watercolours which illustrated the Weezie books.

The orchard and the moor were still there, but strings of phantom light wound between the trees. Shapes danced a midsummer gavotte. Faces formed in the interplay of the trees and the flowers and the light. It was as if music were playing, setting her inner ear a-throb, rhythms syncing with the tides of her body. But there was no sound, just a burst of clarity.

‘We should go out there,’ she said.

The French windows opened by themselves. A shimmering curtain hung above the crazy paving. Tim ran out first, dragging Jordan by her hand. They plunged through the curtain as if it were a waterfall, and joined the others in the orchard, the others who were indistinct but definite.

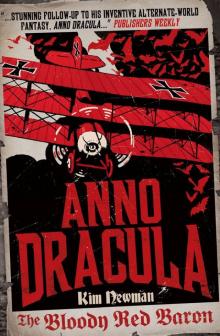

The Bloody Red Baron

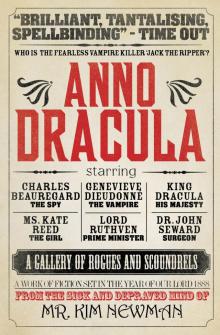

The Bloody Red Baron Anno Dracula

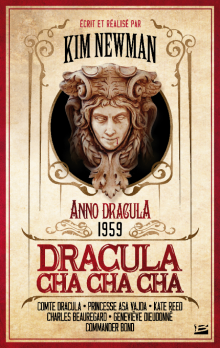

Anno Dracula Dracula Cha Cha Cha

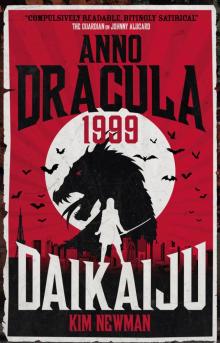

Dracula Cha Cha Cha Anno Dracula 1999

Anno Dracula 1999 Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles Angels of Music

Angels of Music The Man From the Diogenes Club

The Man From the Diogenes Club Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Night Mayor

The Night Mayor Back in the USSA

Back in the USSA Jago

Jago Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes

Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes The Quorum

The Quorum Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories

Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories Life's Lottery

Life's Lottery The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School

The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School Anno Dracula ad-1

Anno Dracula ad-1 The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2

The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2 An English Ghost Story

An English Ghost Story The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School

The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School The Other Side of Midnight

The Other Side of Midnight Bad Dreams

Bad Dreams Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters

Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918

The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918