- Home

- Kim Newman

An English Ghost Story

An English Ghost Story Read online

Contents

Cover

Also by Kim Newman

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Spring

Weezie and the Gloomy Ghost

Moving Day

Settling In

Ghost Stories of the West Country

Chapter Three: ‘THE MOST HAUNTED SPOT IN ENGLAND’

After Midsummer

Journal of a Victorian Gentlewoman

Towards Autumn

Autumn

About the Author

Available now from Titan Books

ALSO BY KIM NEWMAN AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

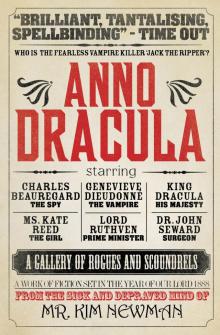

Anno Dracula

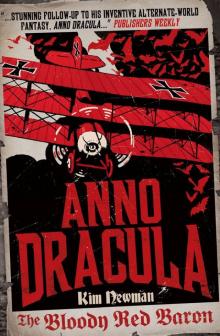

Anno Dracula: The Bloody Red Baron

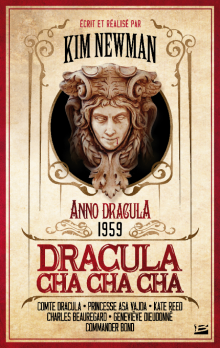

Anno Dracula: Dracula Cha Cha Cha

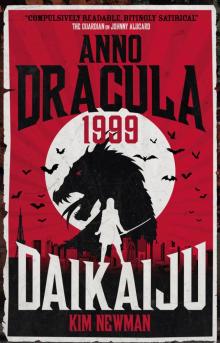

Anno Dracula: Johnny Alucard

Professor Moriarty: The Hound of the D’Urbervilles

Jago

The Quorum

Life’s Lottery

Bad Dreams (December 2014)

The Night Mayor (April 2015)

An English Ghost Story

Print edition ISBN: 9781781165584

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781165591

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: October 2014

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Kim Newman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2014 by Kim Newman

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers.

Please email us at: [email protected]

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

titanbooks.com

For Helen

Spring

They would fall in a clump, like ripe apples. Mother, father, daughter, son. Touched by the charm, their persistent – though thinned – love would flare. As only once before, at the birth of baby Tim, the family would be a whole, united by fiercely shared feeling. Things that had seemed important would be trivial, and things that had seemed negligible would be potent.

The Hollow awaited the family with a welcome. It needed them. Unpopulated, it tended to drift. Without people in residence, it might disperse on the winds. That afternoon, the place was on its best behaviour, spring green promising summer gold.

* * *

When Dad bought a Mercedes-Benz A-Class hatchback, Jordan’s brother Tim had called it a ‘hunchback’ and the car had been ‘the hunchback’ ever since. Dad, proud of his purchasing power, resisted the name for a while, but eventually gave in.

For the long drive to the West Country, Jordan had made a mix tape of season-specific tracks: ‘April in Portugal’, ‘Spring Fever’, ‘Apple Blossom Time’, ‘Springtime for Hitler’. If she had to spend a whole day with her parents and brother, hitting the road at an unreasonable six in the morning, she needed a mental cushion.

On the motorway, beyond range of GLR traffic reports, Dad made a show of being willing to give her tape a listen. Jordan relaxed in the back seat, as her music opened what felt like a cage. After a couple of tracks, the mood in the hunchback turned sour.

‘No one your age can really like this antique crap,’ said Mum, over Judy Garland’s ‘April Showers’. ‘It’s not natural. I wasn’t born when this was recorded.’

Like a weasel, Tim backed Mum up, though he was really too fixated on his Game Boy to register anything outside his bubble of kill-fantasies.

‘Da-ad,’ Jordan appealed.

‘I have to concentrate, Jord,’ he said.

Aptly, Sarah Vaughan sang ‘Spring Will Be a Little Late This Year’.

‘Our daughter has the musical taste of a sixty-year-old drag queen,’ Mum told Dad. ‘One day, she’ll make someone a wonderful fag hag.’

‘What’s a “fag hag”?’ asked Tim.

‘Never mind, Timmy. I’m calling a family vote. Hands up who wants music from this decade.’

Mum put up her hand and so did Tim. Jordan folded her arms, angrily. Dad shrugged, while still holding the steering wheel. Mum declared two for, one against and one abstention. Jordan’s cassette got ejected.

As navigator, Mum controlled the in-car entertainment. She set the tuner to the kind of non-antique crap someone Jordan’s age was supposed to like.

‘This is definitely more now,’ said Mum, pretending to enjoy rap. Jordan thought the track was called ‘Poppin’ a Cap in Mah Bitch’s Skull’. Mum shook her head just out of time to ranted misogyny.

‘Aren’t you supposed to be a feminist?’ she mumbled.

Mum turned round and glared at her. Tim made a gun-finger and popped it at Jordan. When her little brother grew up thinking violent killer pimps were heroes, it wouldn’t be her fault.

She had known this would happen… but she’d still spent several hours compiling her spring mix.

Jordan had resisted this jaunt, but Mum and Dad made a show of including her – and even Tim – in discussions about the move out of the city. The ultimate threat was that if she didn’t take part in viewings, she couldn’t complain about the house they wound up stuck in.

Her parents were striving heroically to keep their own rows about the proposed move to a strained minimum so as to present a united front to the kids. ‘You’ll be living there too,’ one or other of them would say when Jordan’s attention wandered from the sheaves of listings provided by rural estate agents. She always had to bite her lip to keep quiet about her secret plan. She wasn’t going to stay in the backwoods. Once she had her A levels, she would head back to London, get a flat with Rick and find a university place in the city. She’d secretly spent her sixteenth-birthday money on a streamlined art deco kettle. Still boxed under her bed, the Alessi would come out when she was setting up her own home. The best thing about this family exodus was that a year from September, she’d be living over a hundred miles away from the rest of them.

After turning off the motorway, they found themselves driving along winding lanes, craning to make out contradictory signposts for oddly named hamlets. The level of tension ratcheted. Dad held back sharp comments about Mum’s map-reading skills. Today, they were scheduled to view four places around Sutton Mallet, a village in Somerset that was clearly marked but elusive. If you wanted to get there, it seemed you shouldn’t start from here.

‘This map must be out of date,’ said Mum at last, giving up.

‘More likely, it’s too new,’ said Jordan, pointedly. ‘These roads haven’t changed in hundreds of years. Perhaps the map-makers are embarrassed by how antique they are.’

Mum gave Jordan one of her cold looks. Jordan sank back, chafing her shoulder against her seat belt.

‘Sector fifteen cleared,’ Tim said. ‘All hostiles liquidated.’

The beep-beep-beep of Ti

m’s handheld device, a mild irritant three hours ago, was now as painful as regular tapping against an exposed dental nerve. He reported his kill-count every few minutes. His thumbs apparently made him the premier mass-murderer of the age, though he claimed his genocides were justified in a time of war.

Fifty minutes late, in a collective bad mood, they arrived at the first viewing. They piled out of the hunchback. Jordan had chosen a sleeveless blouse for the journey. April chill ice-stroked her bare arms.

The place was a tip. Described as ‘in need of renovation’, the house was a derelict shell on a bankrupt farm. Vast sheds still stank of cattle carcasses. The business had been wiped out by mad cow disease. They stood about, depressed by the cheery chatter of Rowena Marion, the estate agent handling their first two viewings.

‘It’s ghastly,’ said Jordan, loud enough for Mrs Marion to hear. ‘Like an extermination camp for cows.’

Mum looked as if the criticism were aimed directly at her, which it was. All the places would be like this. Jordan had dragged herself out of bed before dawn for an agonising waste of time.

‘I think it’s a “no”,’ said Dad, understating.

‘Early days yet,’ shrugged Mrs Marion, who must have known the farm was unspeakable but still thought it worth showing in the hope the townies were cracked enough to go for it. ‘This is the first place you’ve seen, yes?’

Dad admitted that it was.

‘I think you’re going to love Clematis Cottage,’ Mrs Marion confided, blithely. ‘Follow me and have a look-see.’

The next viewing was a dear little cottage in the village itself. What the listing concealed was that there was no driveway from the road to the ‘extensive adjoining property’ and no suitable place to park within a hundred yards. They cruised past the place, momentarily struck by its picturesque qualities. By the time Dad found a half-hearted lay-by on the other side of the village green, they knew it was a loser.

Trudging back along a grassy verge, Jordan had to lean into a prickly hedge when a tractor passed. Mrs Marion, not ready to give up yet, was there before them, on foot.

The owner – an eighty-year-old keen to move into a nursing home with the fortune he had been told he would realise on his property – loitered like an eager puppy, promising tea and chocolate digestives. Jordan sympathised, but it was cruel to inflate his hopes. They were in and out before the kettle whistled.

They left Mrs Marion – the pensioner should feed her poisoned biscuits – and had a grim pub lunch, saying little about the show so far. Dad had a pint of the local bitter, which was stronger than he expected. Mum had to take over the driving for the afternoon. Not hungry, Jordan couldn’t even finish a packet of salt-and-vinegar crisps.

Next up was a new estate agent, Poulton and Wright. And a place even further outside the village than the hell-farm.

In the back of the car, Jordan looked at the photocopied listing. The property they were to see was called the Hollow. The photograph didn’t give anything away; in it, she could hardly see the house for the trees.

‘Don’t get your hopes up, folks,’ said Dad as they turned off the main road. ‘This was always the long shot.’

Mum and Dad were tense after the dud viewings. Each was storing up blame for the other to shoulder. When a thing failed to work out, no matter the degree of shared initial enthusiasm, it automatically became sole intellectual property of someone else.

They drove down a single-lane road across flat moorland. From a long way off, they saw trees and what looked like the tips of towers.

A car stood on the verge by the open gate of the property. A youngish man, cagoule over pin-striped trousers, waited, leaning against the gate-post. As Mum fussily parked, Jordan looked over the new estate agent. He had spots and the too-ready smile she’d distrusted in Rowena Marion.

But the Hollow was different from Kow Kamp Funf and Clematis Cottage.

Jordan saw it all at once, from the road, and was certain. This was the place. It was like her first kiss, Doris Day’s ‘Que Sera Sera’, the taste of strawberries, her car accident. Instant and all-encompassing, wondrous and terrifying, a revelation and a seduction.

Zam-Bam, Alla-Ka-Zamm!

The strangest thing was she knew her parents felt the same. Mum actually turned and smiled at Dad, who let his hand stray to her wrist for the tiniest of intimate squeezes. Tim looked up from his game, the Elvis lip-curl he’d shown the loser places replaced by open rapture.

‘Kew-ell,’ said Tim.

Jordan was caught up in the spell.

Just this once, nothing else mattered. Her mind was settled in. The shock passed and she got comfortable with the feeling. It was like coming home.

They got out of the hunchback in a tangle and overwhelmed the agent. If he expected city folk to keep their cards to their chest and strike a hard bargain, he was surprised.

‘I love it,’ said Mum. The shift was miraculous: suddenly, she was relaxed and open, uncontrollably smiling. ‘I just love it.’

Jordan saw she had been wrong. The spotty agent’s smile wasn’t fake. Of course, he had known. He had been waiting by the Hollow for a few minutes, and he was familiar with the property. He could feel it too.

The charm.

This was what they needed. A new place, to start all over again, to put the past behind them, to build something. Yet an old place, broken in by people, with mysteries and challenges, temptations and rewards.

They might as well cancel the remaining viewing. ‘I’m Jordan,’ she imagined herself saying to her new friends, ‘I live in the Hollow.’ No, ‘I’m from the Hollow.’

Was the Hollow the house or the land? The name was misleading. Weren’t hollows dents in hills or woods? The property rose a little above the surrounding moorfields. An island that had come down in the world, it still refused to sink into the Somerset Levels.

Her arms didn’t feel cold. A million tiny dandelion autogyros swarmed on warm winds.

‘Brian Bowker,’ said the agent, ‘from Poulton and Wright’s.’

His spots were mostly freckles, though some had whiteheads. He looked as if he was blushing all the time, perhaps a handicap in his business. Unlike Rowena Marion, he didn’t try to hide his West Country accent. He didn’t sound like a yokel, though; it was just a way of talking, a burr.

Dad shook hands with him.

‘This is the Hollow,’ said Brian Bowker, standing aside and making a flourish as if signalling stagehands to haul open the curtains.

Tim had to be restrained from running. Jordan did the honours, hugging her little brother with a wrestling hold. Mum and Dad put arms around each other’s waists and a hand each on a child’s shoulder, as if for a family portrait.

‘We’re the Naremores,’ said Dad. ‘I’m Steven, this is my wife Kirsty, and our children, Jordan and Tim.’

‘Pleased to meet you all,’ said Brian Bowker.

‘I think this is it,’ said Mum, out loud.

The agent’s smile became a grin. ‘You ought to look closer; not that I should say that.’

‘We will, old man,’ said Dad, ‘but I think Kirst is right. I can feel it. Have you sprinkled fairy dust about the place?’

For once, Jordan wasn’t embarrassed by Dad. She knew what he meant. It wasn’t just the spring-blossom; the air seemed to dance. This was the season of the songs, the happy songs about love blooming with the greenery, not the melancholy songs of faded flowers remembered in fall.

The house stood in the middle of a roughly square patch of land, boundaries marked not by hedges or walls but still ditches from which grew bright green rushes. A moat ran alongside the road and the Hollow had its own bridge, wider than it was long, for access. Mum, cautious after the dispiriting fuss at Clematis Cottage, had parked on the road. That felt wrong: they should have driven through the gate and across the bridge, up to the barn, which was large enough to garage a fleet of cars.

Apple trees grew in what Jordan supposed was a deliberate pattern. The la

rgest lay on the ground, roots exposed like a display of sturdy, petrified snakes, hollowed-out body sprouting a thick new trunk, fruiting branches stretching upwards. Tim was enchanted by this marvel, which had been smitten but survived. He had to be called away from exploring before he disappeared entirely inside the wooden tunnel of the original trunk. A couple of trees beyond the house, at the far edge of the grounds, were too close together, upper branches entangled and entwined, like giants kissing.

‘The property used to be called Hollow Farm,’ said Brian Bowker, consulting his clipboard, leading them along a paved path that wound through the trees. ‘It goes back as far as there are parish records, to the Middle Ages. In the nineteenth century, the surrounding fields were sold off to one of the big local farmers and it became just the Hollow. The householders kept only this small apple orchard. You’ll still get all the cookers and eaters you need.’

Jordan could hear the trees. They moved, very slowly. Each leaf, twig, branch and trunk was rustling or creaking, whispering to her. There were trees all over London, but any sounds they made were too faint to be heard above traffic and shouting. City trees were furniture, but these were living things; worlds in themselves, populated by insects, birds, squirrels.

‘In the barn, there’s a cider-press,’ said Brian Bowker, ‘disused since the thirties. It’d cost a fortune to fix, I’m told. A shame. Miss Teazle, the last owner, didn’t work it, but liked having it there.’

The walk was further and the house bigger than Jordan had thought they would be. The house stood on raised stone foundations – Dad said something about a high water table and flood country – and was an obvious patchwork of styles and periods. Matched follies, the towers seen from the road, rose to either side, above a greenish thatched roof, topped by hat-like red tile cones with gabled Rapunzel windows. Aside from the towers, it was a farmhouse built at twice life-size. The ordinary-scale front door looked tiny. Ivy had been encouraged to grow, perhaps to cover the jigsaw-sections of red brick, white plaster and grey stone. Over the centuries, parts of the house had been replaced when they collapsed or people got tired of them. It had grown independent of any architect’s designs or council’s planning permission, evolving to suit its inhabitants.

The Bloody Red Baron

The Bloody Red Baron Anno Dracula

Anno Dracula Dracula Cha Cha Cha

Dracula Cha Cha Cha Anno Dracula 1999

Anno Dracula 1999 Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles Angels of Music

Angels of Music The Man From the Diogenes Club

The Man From the Diogenes Club Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Night Mayor

The Night Mayor Back in the USSA

Back in the USSA Jago

Jago Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes

Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes The Quorum

The Quorum Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories

Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories Life's Lottery

Life's Lottery The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School

The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School Anno Dracula ad-1

Anno Dracula ad-1 The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2

The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2 An English Ghost Story

An English Ghost Story The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School

The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School The Other Side of Midnight

The Other Side of Midnight Bad Dreams

Bad Dreams Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters

Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918

The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918