- Home

- Kim Newman

Jago Page 6

Jago Read online

Page 6

‘Meeting’s at six, Einstein,’ he reminded. ‘If we’m not there, James’ll cross us off the lists. Youm know he don’t like you.’

‘Six’s not for hours, thicko.’

‘This’s boring.’

‘No, ’t ain’t.’

That was it. No more discussion needed. Terry wasn’t bored, so there was no shifting him. Terry fiddled with their dad’s binoculars, trying to get them in focus. The little wheel was missing, so he had to get his finger in and work a cog with a nail.

Teddy didn’t care either way about the Gosmore Farm people, but Terry fancied her and hated him. Terry said he must be a poof. Hazel wore shorts and a halter most days, and had good legs and a flat stomach. For a week, Terry had been thinking aloud, laboriously trying to come up with a scheme to get the boyfriend out of the way so he could have a crack at chatting Hazel up. Some hope. It was difficult not to laugh at Terry when he was plotting. His plans were so stupid, like the time he wanted to steal a barrel of beer from the Valiant Soldier. They wouldn’t have been able to lift it, let alone drink it.

Watching Gosmore Farm really was boring. Hazel was mostly out of sight in the old cow shed making pots. She only ever came out for meals and an hour or so of sunbathing in the late afternoon. The sunbathing was what got Terry worked up. Sometimes, she lay on her front and untied her halter. From the top of the hill, Teddy didn’t find it much of a thrill. When they first started to watch Hazel and her boyfriend, Terry had reckoned they’d take drugs and have it off in the garden. Terry said Hazel was probably a nympho. Terry had a thing about nymphos. According to Knave and Fiesta and him, nymphomania was as common as hay fever. Considering most of Terry’s ideas about women came from the times when Sharon couldn’t find anything better, Teddy supposed his brother’s delusions were understandable. However, he still considered nymphomania a mythical condition, like the curse of the werewolf.

It occurred to Teddy that his brother might be a werewolf. Terry had a thick pelt on his legs and chest, his eyebrows joined over his nose, and he did a lot of growling.

Any hairs on his hands, however, Teddy put down to something else Terry did a lot of. Terry growled now. Hazel and her boyfriend were out of sight.

‘Bet they’m going to have it off tonight,’ Terry said, pointing his shotgun at the house, taking an elaborate sniper’s aim. ‘Pow!’

‘Le’ss go, Einstein.’

Finally, Terry stirred.

‘I know a short cut,’ he said, and Teddy’s heart took a high dive. For someone who’d spent his whole life in Alder, Terry was incredibly unable to find his way around the woods. But he always tried to come on like Indiana Jones.

Teddy had only come out with his brother because it was even more boring at home. Dad was off working for Old Man Maskell, and Mum just wanted to watch soap serials or quiz programmes on the telly. This summer, Teddy was waiting for his exam results. His teachers said he’d have no trouble getting into college. Terry had left school as soon as he could and never taken exams. Even the army wouldn’t take him, and the farmers all knew enough about him to give him only seasonal work. He got his booze, fag and rubber-johnny money from under-the-counter jobs.

‘We’ll be there in five minutes,’ Terry said, pushing into the undergrowth, Teddy unenthusiastically at his heels. As it turned out, the one thing that thrived on this year’s weather was the common bramble. The footpath was clogged with a tangle of vegetable barbed wire. ‘C’mon, thicko,’ his brother ordered.

Teddy had tried to be as mean and stupid as Terry, but couldn’t carry it off. He got interested in his lessons and was pleased when he did well. Most of the things Terry and his mates did or wanted to do struck Teddy as being boring as well as stupid. Terry sometimes said he could set Teddy up with Sharon, and that wouldn’t be boring. Teddy did not doubt it. The problem was talking to her before and afterwards. Secretly, Teddy still fancied Jenny Steyning. No one had seen much of her since she got religion.

Finally, after much scratching, they reached the Agapemone property, only to find a recently reinforced hedge too high to climb and too thick to breach. With some ill feeling, Terry let them give up and double back to the road. By the time they arrived, the meeting had started. On a dead patch of grass just by the Gate House, about twenty teenagers from Alder and the surrounding villages were sitting, cross-legged or sprawled out, paying attention as James Lytton addressed them. They were mostly lads, with two or three girls mixed in.

The man from the Agapemone paced, ticked off points on his fingers, repeated himself to add emphases, and made pointed jokes as if explaining the ins and outs of the D-Day landings to a roomful of army officers. He sounded like someone from a war film as well, his accent not really posh but not normal either.

Everyone else had cans of beer. James had laid on refreshments for the meeting, but they had run out before Teddy and Terry got there. Terry took this badly, and thumped his brother’s arm to establish whose fault it was.

‘Settle down at the back there,’ said James, like a teacher.

Terry unshouldered his gun and squatted in sullen silence near Kevin Conway and Gary Chilcot, and Teddy had to take some ground near Allison, Kev’s creepy, skinny sister. At primary school, Allison had bullied all the boys and, once or twice, had slapped Teddy until he cried. Now, she had long black hair, big black eyes and a worse reputation than any boy in the village. Terry said Allison fancied Teddy, and would torment him with it. Allison crept into his nightmares sometimes.

‘What have we missed?’ asked Teddy.

‘Nothing,’ said Kev. ‘Same speech as last year.’

‘Would the neanderthals who’ve just discovered the power of speech kindly refrain from using it while I get through this, please? Then we can all get in the pub earlier.’

A beery cheer went up, and everybody looked dangerously at Teddy and Terry.

‘Thank you very much,’ James said. ‘Now, back to the agenda. Item nine: the weapons policy. By now, you should know this one. There are a lot of dickheads in this world, and plenty of them turn up here with nothing better to do than make trouble. We try to weed them out, but we can’t eliminate them altogether. What we can do is ensure they aren’t lugging any heavy artillery. Look for knives, baseball bats, suspiciously sturdy walking sticks, catapults et cetera. We’ve never had hassles with firearms or crossbows before, but be on the lookout. There’s always a first time. No one turned up with a stun gun until last year. There will be various people who, for one reason or another, will be in costume. All the legitimate theatrical groups will be blue-badged. They’ve promised us that any swords will be cardboard and rayguns nonoperational. As for anyone else, Vikings will be relieved of their axes, ninjas of their chain sticks. There is no negotiation on this issue. If you see anyone violating our weapons rule, come to me or any of our security people, and we’ll deal with the offender. Don’t try to be a hero and handle the confiscation yourself. As Gary will tell you, it just ain’t worth it.’

Gary Chilcot rolled up his sleeve and traced his scar with an index finger. The year before last, he’d tried to take a sharpened screwdriver off some paranoid kid and wound up with a tetanus infection. There were some humorous expressions of disgust around him.

‘Joking aside, be on the watch,’ James continued. ‘We’ve got a secure area marked in red on your maps, where all the little cowboys can hang up their gun belts. We were lucky last year, electric shocks aside, and had relatively little trouble. Let’s not let things slip. Item ten: entry points. We’ve heavily pre-sold this year to take the pressure off the gates, but we’ll still be taking plenty of admissions in cash. Now, off the record, I’d far rather a few canny punters sneaked in for nothing than have two-mile queues tailing back through the village. The order of the day is to keep things moving. We’ve got five entry points to the estate, if you’ll look at your maps…’

Teddy and Terry didn’t have maps yet, but Allison let Teddy share hers. He was only half listening anyway, sin

ce he’d heard most of it last year and it didn’t really apply to him. He assumed he’d be working in the crèche again. It was a laugh, and the kids liked his funnies.

The Gate House was a squashed cottage by the estate wall. James Lytton lived alone in it, well away from the Manor House and the loonies. Teddy couldn’t understand why such a straight-up bloke was with Jago’s crew. There were a few of them at the meeting, smiling placidly without apparently hearing anything, dressed smartly but out of style. He recognized Derek, who’d been in charge of the crèche last year. Teddy had got on all right with him, but there was something missing. They weren’t quite zombies, like most people said, but they weren’t living in the real world either. Derek was with his girlfriend, a loud and matronly woman, and two others, a muttering girl whose head was always bowed in prayer, and (his heart clutched) Jenny Steyning.

Her parents were up in arms about Jenny joining the Agapemone and had called in a lawyer, but she was over sixteen and could do what she liked. She didn’t seem to have changed much, but then she had always been cool. In a long white dress, she looked like a sacrifice waiting for a hungry dragon. All she needed was a floral headband.

‘…so, any of that, and we’re empowered to take their badge, give them a partial refund, and kick them out. And I do mean kick. Item fourteen: the Manor House. It’s off limits. No arguments, no special circumstances. Most of the Brethren will be involved in one way or another with the festival, but Mr Jago doesn’t want the event to shake up his routine. You may not share his beliefs, but this is a religious institution and that demands some respect. The general public are to be kept away from the house, and from all buildings on the estate not designated festival facilities. That includes where I live, by the way. Item fifteen: our old favourite, the bogs. We had a fiasco last year, so we’ve been rethinking our whole lavatorial setup, and…’

Each year the festival grew, and the preparations for it became more elaborate. Organizing it was a lot like setting up the invasion of France. At first, the Agapemone had tried to make do with the Brethren, but they hadn’t even been able to cope with the much smaller event it had been. Now there were maybe a hundred local people involved, and professionals from outside were being brought in to handle everything from food to first aid. There must be a lot of behind-the-scenes work going on. Teddy wouldn’t be at all surprised if the festival was making a lot of money for a few people. With this year’s lump of cash, he ought to have enough to buy a moped, and if he, a minor cog in the machine, was being so well oiled, the higher-ups must be bathing in it.

No one in Alder said much about the Agapemone itself any more. These days, the festival was much bigger news than the people behind it. A lot of the old farts were against the event, but it went ahead every year because it was too sweet for many local businesses to turn down. Douggie Calver, who owned the apple orchards and cider presses out on the Achelzoy road, made the bulk of his annual profit during festival week. His stall was always the busiest on the site. When Jago first came to the village, opinion had been split as to whether he was daft or dangerous. Now, people had got used to the Agapemone. Jago himself was so seldom seen he was almost forgotten. When Jenny joined the Brethren (Sistren?), Teddy had thought a bit about it and more or less decided there was something scary about the Agapemone. What disturbed him was that too many of the people connected with the place were obviously not crackpots. If someone like James was involved, he couldn’t write the setup off as a congregation of God Squad nutters. And the festival was run too smoothly to be the work of a bunch of loonies.

Usually, with the locals, the Brethren didn’t even mention their beliefs, but if pushed they’d come out with some serious strangeness. Last year, Derek had tried to explain it during a lull in the Lost Child season, but clammed up when Teddy asked him for his personal feelings. One thing he’d gathered was that, although they tried not to with outsiders, among themselves the Brethren of the Agapemone referred to Anthony Jago as ‘Beloved’. That had a nasty ring to it.

Maybe Jago was related to God after all, he thought, something between a shiver and a shrug shaking his shoulders.

‘…finally, the specific jobs. You’ve all been given assignments based on the questionnaires you filled in and your performances, if any, in previous years. No arguments please, my decision is final. I’ve had the job lists word-processed, and Sister Karen will now distribute the print-outs. So, let’s do it to them before they do it to us.’

There was dutiful laughter from the four or five people who remembered Hill Street Blues while a pretty girl fussed with the hand-outs. She slit open a taped cardboard box with a scalpel and took out an armload of papers, which she passed in wedges to the other Sisters. Quickly, the stapled documents were scattered among the crowd.

Jenny gave the papers to the little group Teddy was in. He said hello to her, and she smiled back without saying anything. He knew she’d heard, but she was treating him as if they’d never met.

‘No one home,’ Allison said, tapping her forehead as Jenny went on to the next group. ‘Jago’s been fucking her brains out. They’re all gone.’

It was as if Allison had started slapping him again; and he was turned back into a little crying kid, snot moustaching his face, hot tears on his cheeks. He recovered, and made himself look at the paper.

He was in the crèche again, but not with Derek. Jenny was also (his heart clutched again) down for the duty. He looked up and James was there. Everyone was standing up, comparing jobs, moaning or crowing.

‘You did a good job last year, Teddy,’ said James. ‘You should be able to handle the whole thing this time. You’ll have a full roster of volunteer mums under you. You might talk with Derek in the pub later, and get the benefit of his experience.’

‘Thanks, James. I ’preciate this.’

‘That’s okay. You’re good with kids. Just don’t let your idiot brother screw it up for you again.’

Loyally, he didn’t say anything. Terry was bitching because he was a lowly member of the car-park crew, which would keep him away from the music and whatever else was going on. Mainly, he would miss the drink, the dope and the nymphos. He’d done some pilfering last year. He hadn’t been found out for a change, but Teddy reckoned James must’ve had his eye on Terry and made a few good guesses. The news made Terry feel mean, and he wanted to take it out on Teddy.

‘Youm with they stupid kids, then?’

‘It’s okay, it’s a good laugh.’

Terry tried to sneer. ‘Raaahh! You’m a clown, my boy, a stupid clown.’

Last year, the kids had got into face-painting, and had coloured Teddy like a clown.

‘Leave off him, Car Park King,’ said Allison, which shut him up instantly. ‘You’re a one to talk. Everyone knows you’re thicker’n two short ones, an’ twice as dense.’

Terry tried to laugh but it turned sour in the back of his throat. His brother was scared of Allison. She had once done something to him in the copse by the primary school, something that still made him go white and treat her with respect. They had all grown up since primary school, but some things never change.

‘We’re off down the Valiant Soldier,’ said Kev. ‘You boys comin’?’

‘Might as well,’ said Terry.

Teddy was looking around, looking for someone. ‘Teddy?’ asked his brother. ‘You comin’ or goin’ or what?’

‘What?’

‘Pub. You comin’ or goin’?’

‘Oh, yurp. Comin’. I was just thinkin’.’

Kev laughed. ‘Your brother’ll go blind if he keeps up all this thinkin’, Ter. Gonna bust his brainbox proper.’

They left in several groups. Teddy looked back. Through the gates of the Agapemone, he could see the lawns in front of the Manor House. Jenny was crossing towards the huge doors. She was with people, but he could recognize her by the white dress and blonde hair.

In his head, he kept hearing Allison. ‘No one home.’ His memory added spite to every syllable. ‘

Jago’s been fucking her brains out.’

His mind made up pictures to go with the words. Jenny, in and then out of her white dress, flowers falling from her hair. And Jago, half the darkly handsome man Teddy had seen several times, half the leather-winged dragon he had imagined earlier, folding her in his long, skin-sleeved arms, piercing her with a scaly, red-tipped cock. As they rutted, the life in Jenny’s eyes dimmed.

‘Jago’s been fucking her brains out,’ Allison had said. ‘They’re all gone.’

7

The main hall of the Agapemone was both chapel and dining room. The Brethren were assembled for the evening meal, but the great space felt empty. It was as if a light source had been removed; the absence of Him was as tangible as His presence. When Wendy was out of His gaze, the darkness crept in. Old panic stirred in the depths of her soul, waking like Leviathan, preparing to strike for the surface. They were very close to the End of Things, and she must be strong in her faith in the Beloved Presence. Sometimes she dreamed she was on an island in the mists, surrounded by strange shapes, and He was far from her. It was so easy to lose her hold.

She had come to the meal direct from the meeting, with Sister Marie-Laure and the new Sister, Jenny. She was struggling to put down the pique she felt at Derek’s desertion. He hadn’t needed to go to the pub with Lytton and the outsiders, but it wasn’t her place to instruct him in the path of perseverance. And his was not the absence she felt most keenly.

‘Beloved won’t be joining us this evening,’ Mick Barlowe announced as she took her place. ‘He’s tired, and is having His meal in His room. I’ve been asked to read His lesson.’

Wendy looked at His chair, no place laid before it, and at the wings of the altar which stood in the darkness beyond. In her memory she saw Him as a golden shadow presiding over the meal. Loving everyone through His words. The memory flashes were brief, and instantly gave way to the dark. When she was away from Beloved for even a few hours, Wendy found it hard to remember His face in detail. In her mind, He receded into His light and became indistinct.

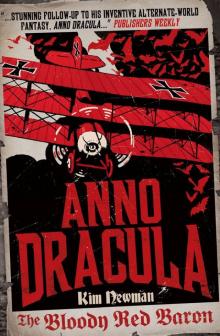

The Bloody Red Baron

The Bloody Red Baron Anno Dracula

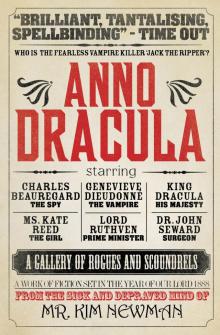

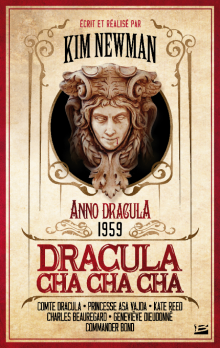

Anno Dracula Dracula Cha Cha Cha

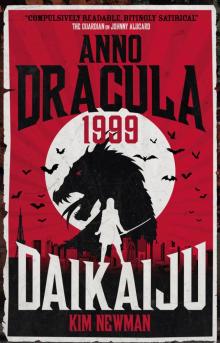

Dracula Cha Cha Cha Anno Dracula 1999

Anno Dracula 1999 Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles Angels of Music

Angels of Music The Man From the Diogenes Club

The Man From the Diogenes Club Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Night Mayor

The Night Mayor Back in the USSA

Back in the USSA Jago

Jago Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes

Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes The Quorum

The Quorum Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories

Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories Life's Lottery

Life's Lottery The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School

The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School Anno Dracula ad-1

Anno Dracula ad-1 The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2

The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2 An English Ghost Story

An English Ghost Story The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School

The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School The Other Side of Midnight

The Other Side of Midnight Bad Dreams

Bad Dreams Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters

Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918

The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918