- Home

- Kim Newman

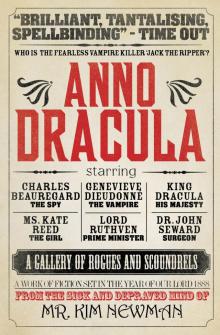

Anno Dracula ad-1 Page 5

Anno Dracula ad-1 Read online

Page 5

Baxter had adjourned before midnight, and reconvened the inquest this morning. Now evidence from the post-mortem was available, and today’s business mainly concerned a succession of medical men, all of whom had crammed themselves into Whitechapel Workhouse Infirmary Mortuary to examine the mortal remains of Lulu Schön.

First came Dr George Bagster Phillips, the H Division Police Surgeon – well known at Toynbee Hall – who had done the preliminary examination of the body in Chicksand Street and performed the more detailed post-mortem. It boiled down to the simple facts that Lulu Schön had been heart-stabbed, disembowelled and decapitated. It took much desk-banging to quieten the outrage that followed these not unexpected revelations.

By law, inquests had to be held in public places and be open to the press. From the several appearances Geneviève had made as a witness in connection with the deaths of paupers in Toynbee Hall beds, she knew the only audience was usually a bored stringer from the Central News Agency, with the occasional friend or relation of the deceased. But the lecture hall was even more thickly populated today than it had been yesterday, the benches as heavily burdened as if Con Donovan were on the stage, rematching with Monk for the Featherweight Title. Aside from the reporters hogging the front row, Geneviève noticed a gaggle of haggard mainly un-dead women in colourful dresses, a scattering of well-dressed men, some of Lestrade’s uniformed juniors, and a sprinkling of sensation-seekers, clergymen and social reformers.

In the centre of the room, spaces all around unoccupied despite the surplus of attendees, sat a long-haired vampire warrior. Not a new-born, he wore the uniform, including a steel breastplate, of the Prince Consort’s Own Carpathian Guard, augmented by a tasselled fez. His face was withered white parchment but his eyes, blood-red marbles set in the dead waste of skin, constantly twitched.

‘Do you know who that is?’ Lestrade asked.

Geneviève did. ‘Kostaki, one of Vlad Tepes’s hangers-on.’

‘That sort gives me the creeps,’ commented the new-born detective. ‘The elders.’

Geneviève almost laughed. Kostaki was younger than she. His presence was almost certainly not due to mere curiosity. The Palace was taking an interest in Silver Knife.

‘People die every night in Whitechapel, in ways Vlad Tepes couldn’t devise, or live lives worse than any death,’ Geneviève said, ‘yet from one year’s end to the next, London pretends we’re as remote as Borneo. But give them a handful of gory murders and you can’t move for sightseers and prurient philanthropists.’

‘Maybe some good will come of it,’ Lestrade commented.

Dr Bagster Phillips was thanked and dismissed, and Baxter called for Henry Jekyll, M.D., D.CL., LL.D., F.R.S., etc. A dignified, smooth-faced man of fifty, obviously once handsome, approached the lectern and took the oath.

‘Whenever a vampire’s killed,’ Lestrade explained, ‘Jekyll comes creeping round. Something rum about him, if you get my drift...’

The scientific researcher, who first gave a detailed and anatomically precise description of the atrocities, was warm only in the sense that he was not a vampire. Dr Jekyll was self-controlled to a point that suggested a disturbing lack of empathy with the human subject of the inquest, but Geneviève listened with interest – certainly more than that expressed by the yawning reporters in the front row – to the comments Baxter solicited from him.

‘We have not learned enough about the precise changes in the human metabolism that accompany the so-called “turn” from normal life to the un-dead state. Precise information is hard to come by, and superstition hangs like a London fog over the subject. My studies have been checked by official indifference, even hostility. We could all benefit from research. Perhaps the divisions which lead to tragic incidents like the death of this girl could then be erased from our society.’

The anarchists were grumbling again. Without divisions, their cause would have no purpose.

‘Too much of what we believe about vampirism is sheer folklore,’ Dr Jekyll continued. ‘The stake through the heart, the silver scythe. The vampire corpus is remarkably resilient, but any major breach of the vital organs seems to produce true death, as here.’

Baxter hummed and questioned the doctor. ‘So the murderer has not, in your opinion, followed what we might deem the standard superstitious practice of the vampire killer?’

‘Indeed. I should like to put certain facts into the record, if only to provide a definitive contradiction of irresponsible journalism.’

Some of the reporters hooted quietly. A lightning sketch artist sitting in directly in front of Geneviève was deftly portraying Dr Jekyll for reproduction in the illustrated press. He pencilled in some dark shadows under the witness’s eyes to make him look more untrustworthy.

‘As with Nichols and Chapman, Schön was not penetrated with a wooden stake or paling. Her mouth was not stuffed with cloves of garlic, or fragments of communion wafer, or pages torn from a sacred text. No crucifix or cruciform object was found on or near the body. The dampness of her skirts and the residue of water on her face were almost certainly condensation from the fog. It is highly unlikely that the body was sprinkled with holy water.’

The artist, probably the man from the Police Gazette, drew in heavy eyebrows and tried to make Dr Jekyll’s thick but immaculately combed hair look shaggy. He went too far in distorting his subject and, tutting at his overenthusiasm, tore the sheet off his pad, crumpled it into his pocket, and began afresh.

Baxter jotted down some notes, and resumed his questioning. ‘Would you venture that the murderer was familiar with the workings of the human body, whether of a vampire or not?’

‘Yes, coroner. The extent of the injuries betokens a certain frenzy of enthusiasm, but the actual wounds – one might almost say incisions – have been wrought with some skill.’

‘Silver Knife’s a bleedin’ doctor,’ shouted the chief anarchist.

The court again exploded into uproar. The anarchists, about half-and-half warm and new-borns, stamped their feet and yelled, while others talked loudly among themselves. Kostaki looked around and silenced a pair of clergymen with a cold glare. Baxter hurt his hand hitting his desk.

Geneviève noticed a man standing at the back of the courtroom observing the clamour with cool interest. Well-dressed, with a cloak and top hat, he might have been a sensation-seeker but for a certain air of purpose. He was not a vampire, but – unlike the coroner, or even Dr Henry Jekyll – he showed no signs of being disturbed to be among so many of the un-dead. He leant on a black cane.

‘Who is that?’ she asked Lestrade.

‘Charles Beauregard,’ the new-born detective said, curling a lip. ‘Have you heard of the Diogenes Club?’

She shook her head.

‘When they say “high places”, that’s where they mean. Important people are taking an interest in this case. And Beauregard is their catspaw.’

‘A striking man.’

‘If you say so, mademoiselle.’

The coroner had restored order again. A clerk had nipped out of the room and returned with six more constables, all new-borns. They lined the walls like an honour guard. The anarchists were brooding again, their purpose obviously to cause enough trouble to be an irritant but not enough to get their names noted.

‘If I might be permitted to address the implied question raised by the gentleman,’ Dr Jekyll asked, eliciting a nod from Baxter, ‘a knowledge of the position of the major organs does not necessarily betoken a medical education. If you are disinterested in preserving life, a butcher can have out a pair of kidneys as neatly as a surgeon. You need only a steady hand and a sharp knife, and there are plenty of both in Whitechapel.’

‘Do you have an opinion as to the instrument used by the murderer?’

‘A blade of some sort, obviously. Silvered.’

The word brought a collective gasp.

‘Steel or iron would not have done such damage,’ Dr Jekyll continued. ‘Vampire physiology is such that wounds inflicte

d with ordinary weapons heal almost immediately. Tissue and bone regenerate, just as a lizard may grow a new tail. Silver has a counteractive effect on this process. Only silver could do such permanent, fatal harm to a vampire. In this instance, the popular imagination, which has tagged the murderer as “Silver Knife”, has almost certainly got its facts straight.’

‘You are familiar with the cases of Mary Ann Nichols and Eliza Anne Chapman?’ asked Baxter.

Dr Jekyll nodded. ‘Yes.’

‘Have you drawn any conclusions from a comparison of these incidents?’

‘Indeed. These three killings are indubitably the work of the same individual. A left-handed man of above average height, with more than normal physical strength...’

‘Mr Holmes would’ve been able to tell his mother’s maiden name from a fleck of cigar ash,’ Lestrade muttered.

‘... I would add that, considering the case from an alienist’s point of view, it is my belief that the murderer is not himself a vampire.’

The anarchist was on his feet but the coroner’s extra constables were around him before he could even shout. Smiling to himself at his subjugation of the court, Baxter made a note of the last point and thanked Dr Jekyll.

Geneviève noticed that the man she had asked Lestrade about was gone. She wondered if Beauregard noticed her as she had noticed him. From her side, a connection had been made. She was either having one of her ‘insights’ or had gone too long without feeding. No, she was certain. The man from the Diogenes Club – whatever that really was – was materially involved in the affairs of the Whitechapel Murderer, but she could not guess in what capacity.

The coroner began his elaborate summing-up, delivering the verdict of ‘wilful murder by person or persons unknown’, adding that the killer of Lulu Schön was judged to be the same man who had murdered, on 31st of August, Mary Ann Nichols, and, on 8th of September, Eliza Anne Chapman.

7

THE PRIME MINISTER

‘Were you aware,’ began Lord Ruthven, ‘that there are people in these isles whose sole objection to the marriage of our dear Queen – Victoria Regina, Empress of India, et cetera – to Vlad Dracula – known as Tepes, quondam Prince of Wallachia – is that the happy bridegroom happened once to be, in a fashion I shan’t pretend to understand, a Roman Catholic?’

The Prime Minister waved a letter selected apparently at random from the piles of ignored correspondence littering the several desks in his Downing Street receiving room. Godalming knew better than to interrupt one of Ruthven’s fits of loquacity. For a new-born eager to be initiated into the secrets of the elders, close attention to the centuries-old peer was a valuable, indeed indispensable, instrument of learning. When Ruthven talked a streak, volumes of ancient truth disclosed long-forgotten spells of power. It was hard not to be caught up in the force of his personality, to be transported on wings of rant.

‘I have here,’ Ruthven continued, ‘a missive from a miserable society devoted to the thin memory of that constitutionalist bore Walter Bagehot. They tactfully complain that the Prince accepted the embrace of the Anglican Church an indecently short time before he accepted the embrace of the Queen. Our correspondent even goes so far as to suggest Vlad might conceivably not be sincere in his abjuration of the Pope of Rome, and that, with Cardinal Newman as his secret confessor, he has imported the perfidious taint of Leo the Thirteenth into the Royal Household. My curly-haired friend, some dunderheads find it easier to forgive a taste for virgin blood than the drinking of communion wine.’

Ruthven shredded the letter. Its confetti joined that of many other derided documents on the carpet. He grinned and breathed heavily, but there was no trace of his apparent excitement in his milk-white cheeks. It struck Godalming that the Prime Minister’s rages were counterfeit, the impostures of a man more used to simulating than experiencing passion. He strode across the room, making and unmaking fists behind his back, grey eyes like fine-lashed marbles.

‘Our Prince changed his faith before, you know,’ Ruthven observed, ‘and for the same reason. In 1473, he abandoned Orthodoxy and became Catholic so he could marry the sister of the King of Hungary. The manoeuvre won him freedom after twelve years as a hostage at Mathias’s court, and a clear shot at regaining the Wallachian throne his bloody foolishness had lost him. That he stuck by Rome for four centuries afterwards tells you not a little about the man’s innate dullness. If you wish to examine the true soul of conservatism, you should look no further than Buckingham Palace.’

By now the Prime Minister was addressing himself not to Godalming but to a portrait. Its beak-nosed profile was turned towards a balancing picture of the Queen that ornamented the same wall. Godalming had only met Dracula once; the Prince Consort and Lord Protector, then a mere Count going by the name of de Ville, had not much resembled the proud creature captured in paint by Mr G.F. Watts.

‘Imagine the brute, Godalming. Brooding for four hundred years in his stinking wreck of a castle. Plotting and scheming and swearing and gnashing his teeth. Festering in medieval superstition. Bleeding dry uncouth peasants. Running and rutting and raping and rending with the mountain beasts. Taking his coarse pleasure with those un-dead animals he calls wives. Shifting his shape like some were-wolf mountebank...’

Though the Prince Consort had personally sponsored the Prime Minister’s appointment, relations between the vampire elders, formed over the course of centuries, were hardly congenial. In public, Ruthven displayed the expected fealty to the elder who had been King of the Vampires long before he was ruler of Great Britain. The un-dead had been an invisible kingdom for thousands of years; the Prince Consort had, at a stroke, wiped clean that slate and started anew, lording over warm and vampire alike. Ruthven, who had passed his centuries in travel and dalliance, was dragged out of the shadows with the other elders. Some might say that a chronically impoverished nobleman – who once remarked that his title and barren acres in Scotland could buy him a halfpenny bun if he had the ha’pence to go with them – had done well out of the changes. But His Lordship, a man whose title could hardly compare with Godalming’s own, was a complainer.

‘Now this Dracula has his Bradshaw by heart and calls himself a “modern”. He can tell you all the times of trains from St Pancras to Norwich on bank holidays. But he can’t believe the world has revolved since he got himself killed. Do you know how he died? He disguised himself as a Turk to spy on the enemy, then his own men broke his neck when he tried to come back to camp. The seed was already in him, put there by some fool of a nosferatu, and he crawled out of the earth. He is nobody’s get. How he loves his native soil, to sleep in it at every opportunity. There’s grave-mould in his bloodline, Godalming. That’s the sickness he spreads. Think yourself lucky that you are of my bloodline. It’s pure. We may not turn into bats and wolves, my son-in-darkness, but we don’t rot on the bone either, or lose our minds in a homicidal frenzy.’

Godalming believed Ruthven had sought him out and made a vampire of him solely because of his involvement in what was now regarded as an underhanded conspiracy against the Royal Person. When warm, Godalming had personally destroyed the first of Dracula’s British get. That made him a likely candidate for the pike between Van Helsing and that solicitor fellow Harker. He remembered with a shudder the Thor-like blows that drove the stake through his then-beloved Lucy, and felt a poisonous hate for the Dutchman who had persuaded him to such an extreme. He had been criminally foolish and was now eager to compensate. His turning, and Ruthven’s adoption of him as protégé, had saved his heart for the moment, but he was too well aware of the Prince Consort’s capriciousness and capacity for vengeance. And, of course, his father-in-darkness was hardly known for his own constancy or evenness of temperament. If he was to find a secure place in the changed world, he would have to be careful.

‘His ideas were formed in his lifetime,’ Ruthven continued, ‘when you could rule a country with the sword and stake. He missed the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Age of Enlightenment, the

French Revolution, the rise of the Americas, the fall of the Ottoman. He wishes to avenge the death of our gallant General Gordon by dispatching a force of ferocious vampire idiots to ravage the Sudan and impale all who owe allegiance to the Mahdi. I should let him do it. We could well live without his Carpathian cronies draining the public purse. Let a hundred or so of the clods get cut down by canny Mussulmen and left to rot in the sun and we’d have all the barmaids in Piccadilly and Soho flying the Crescent in gratitude.’

Ruthven swept his hand through another pile of letters, and sent up a flurry which descended around him. The Prime Minister seemed barely out of his teens, with cold grey eyes and a dead white face. He betrayed no ruddy flush even when he had just fed. A connoisseur of delicate young girls, he nevertheless chose for his get able young men of position. He distributed his new-born children-in-darkness to government offices, even encouraging competition between them. Godalming, unsuited by his title to menial duties and yet hardly qualified for a cabinet post, was currently the most favoured of Ruthven’s get, serving unofficially as a private messenger and secretary. He had always had a practical streak, a flair for working out the details of complicated plans. Even Van Helsing had trusted him to handle much of the spade-work of his campaign.

‘And have you heard of his latest edict?’ Ruthven held up a scroll of official parchment, bound in scarlet tape. It unravelled, and Godalming saw the copperplate of a palace secretary. ‘He wants to crack the whip on what he refers to as “unnatural vice”, and has decreed that the punishment for sodomy shall henceforth be by summary execution. The method will, of course, be his old reliable, the stake.’

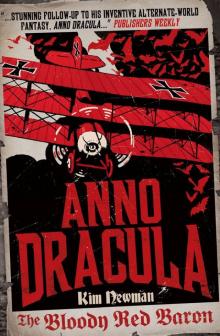

The Bloody Red Baron

The Bloody Red Baron Anno Dracula

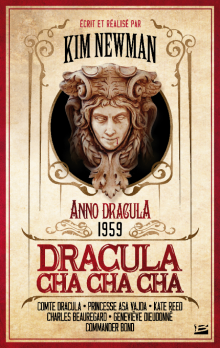

Anno Dracula Dracula Cha Cha Cha

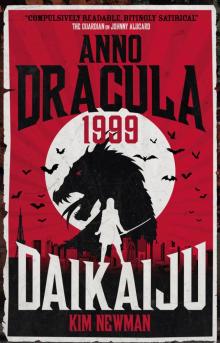

Dracula Cha Cha Cha Anno Dracula 1999

Anno Dracula 1999 Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles Angels of Music

Angels of Music The Man From the Diogenes Club

The Man From the Diogenes Club Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Night Mayor

The Night Mayor Back in the USSA

Back in the USSA Jago

Jago Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes

Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes The Quorum

The Quorum Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories

Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories Life's Lottery

Life's Lottery The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School

The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School Anno Dracula ad-1

Anno Dracula ad-1 The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2

The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2 An English Ghost Story

An English Ghost Story The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School

The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School The Other Side of Midnight

The Other Side of Midnight Bad Dreams

Bad Dreams Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters

Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918

The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918