- Home

- Kim Newman

An English Ghost Story Page 4

An English Ghost Story Read online

Page 4

First, he inspected the perimeter. He began at the bridge, looked over the clean concrete support pillars which had been put in recently. Plants were already swarming up around them, green rust spreading in tendrils. He slid down the thickly grassed slope to the slow-flowing stream and looked under the bridge. He dipped his hand in the cool water. In a pinch, it was potable.

He found an unrusted steel strut which made a perfect hand-hold and slipped under the bridge, curling up and jamming his knees against the concrete underside to keep his feet out of the water. There was just enough space to crawl along, hanging upside down, reaching from strut to strut, without getting wet. Emerging into sunlight, he awarded himself ten merit points for the small manoeuvre but deducted five for forgetting to time himself against his stopwatch. If he didn’t know his time, how could he better it?

Beyond the bridge, he stayed down in the stream-bed and made his way to the corner of the property, where a T-junction fed the ditch around the Hollow. The moat was shallow, a reflecting runnel of green water in the centre of a strip of muddy, reed-thronged marsh. Insects crawled and buzzed, some fabulously strange.

Tim made his way around the ditch, until he was back where he started. The Hollow’s moat consisted of two flowing streams connected by still cross-channels. The moor, neutral territory, was divided into fields by these ditches. Far off, he could see sheep.

His hands and arms were brown now, with grey patches where mud had dried in the sun.

The perimeter secure, he mentally divided the property into quadrants: orchard, garage/barn, house, drive. The garage/barn and the house would warrant extensive individual patrols, but orchard and drive were open territory. At present, the drive was occupied by the movers’ vehicle. Tim found a spot by an outlying tree, in a clump of bushes dotted with tiny yellow flowers. He blended in to watch the removal men at work. Since the secret passage was narrow, they had to lug the bigger items round by a side path and through the glass doors. He was pleased none of them spotted him. They were not potential hostiles, but this was fresh country and he needed the practice. He had to become part of the land.

He thought about the orchard. He felt good about the place. The tree had dropped apples into his hand. An operative could live off the land in that quadrant, find shelter and provisions. Vegetation would conceal him from enemy eyes.

The largest of the trees had fallen once, but grew still. The trunk had split open and its inside was rotted out, but it had survived and flourished. A thick, healthy limb extended from the main trunk, spreading living branches from the hollow bole, sound wood growing from the dead. This was a good place. When prying eyes were gone, he would work with an entrenching tool and make himself a lair. PP had said something about helping Tim build a treehouse, but that wasn’t quite in the plan. He envisioned a hide, which would be secret. From the outside, it must just look like a fallen tree. Hostiles would stroll past without knowing they were mere feet from his lair. He had a code-name ready, Green Base.

The old campaign, the city mission, was over. No victory could be claimed, since it was abandoned before objectives were secured. A black demerit against him, which he would have to work hard to wipe out. Though it had not been his decision, forces had withdrawn and he had pulled out along with the rest of them.

Here, there would be a new campaign.

At the Hollow, there was a chance for G and G. Gold and glory.

A fresh apple fell, nearby. Tim reached out and it slapped right into his hand, a perfect catch.

Earlier, he had shared fruit with the family.

This was just for him.

* * *

The Hollow swallowed everything they had brought from London. When heaved into place by the removal men, their desks and chairs stood out, clashing with what was there. But if Kirsty looked again a few minutes later, she couldn’t tell what was old and what was new – except the obvious Naremore gadgets Miss Teazle had lived and died without: widescreen TV, computers, CD and DVD players, fax, microwave.

Kirsty’s old things, bits of furniture from the flat, were newer than things which had been here for ever, or at least since Louise Teazle was a girl. Decisions must be made soon. Stuff would have to go. Their leaved dining table looked like a sideboard next to the Hollow’s main table, which was long, wide and solid enough for a catwalk.

She was ready to be ruthless. Someone in this family had to be. First for the chop: a dusty five-bar electric heater which stood in the huge fireplace. Its inadequate grille and visibly frayed fabric cord were accidents in the making.

The Hollow was a project worthy of her full attention. She had ideas about how it could be made to work for them. At the moment, Steven thought of it as only a home, but Kirsty saw more, a potential business asset. She wasn’t ready to set out her ideas yet, but when she did they would be stunners.

They already had post, dumped on an escritoire in the passage. She carried it into the main room. Letters had come from electricity, water, satellite TV and telephone suppliers. A technician would be out tomorrow to hook up more phone lines and the satellite dish was due at the end of the week. She glanced at an electoral register form and a set of leaflets from the council and read several cards from people who had received their change-of-address note.

‘You haven’t dropped out of the rat race,’ wrote Bobbie, ‘you’re just running faster than the other rats.’ What had her sister meant by that? Probably nothing; it was widely accepted that Bobbie was barking.

When she picked up a slim packet, borders edged with the self-invented hieroglyphs Vron used on everything, an uneasy plunge of anticipation troubled her stomach. She had no idea how her best friend was really taking the family move, whether she saw it as a betrayal or an abandonment. She turned over the jiffy bag several times, trying to puzzle out runes she knew were impenetrable. To the horror of the Post Office, Vron once sent Steven a birthday parcel blatantly marked ‘contains Anthrax and Poison’, CDs of the metal bands he didn’t like. After a deep breath, she slit open the packet. Out slid a shiny, modern paperback. Weezie and the Gloomy Ghost, first of the Weezie books. Inside the book was an Escher postcard with ‘Luck’ lettered on the back.

Kirsty thought Vron didn’t believe in luck, then remembered her friend’s actual statement was that she believed people made their own luck. Thinking for a moment, she decided it was a fair post-break card, a helpful note – though ‘Good Luck’ would have been less ambiguous. The picture, of impossible lizards climbing impossible stairs, meant something she would puzzle out later. Everything Vron did meant something. The book would be useful. She would re-read it, perhaps aloud to Steven and the kids… though she’d better keep back who it came from. Vron was still a touchy subject at family meetings.

A cream envelope was addressed to ‘The New Owners’. Mr Bernard Wing-Godfrey, President of the Louise Magellan Teazle Society, asked permission to pay a visit to discuss matters relating to the late authoress. He congratulated the Naremores on being lucky enough to live in his heroine’s house.

Did Wing-Godfrey mean Weezie or Miss Teazle?

She hadn’t read a Louise Magellan Teazle in thirty-five years. Suddenly, looking at the little girl on the cover of the book, a penny dropped. Weezie was short for Louise, doubly short for Louise Teazle. They must have called Louise ‘Weezie’ when she was little. Kirsty paged through Weezie and the Gloomy Ghost, looking at the Van Loon illustrations. Hilltop Heights was the Hollow taken off a moor and put on a hill. One picture showed Weezie’s home in full, in the distance beyond the copse where Weezie stood with the transformed Merry Ghost. The two towers were unmistakable. Kirsty wanted to share this with Steven, soon.

She looked around, remembering what she had said on the viewing day, that she could see things from the stories in the big room – what would they call it, the hall? – and all around the house.

Kirsty had never known such a happy place.

And now she lived here.

She had been told about happy

places, but never been able to believe in them. Until the break, Vron had told her that what she needed to do was find a happy place inside herself and move into it when things got too much. Vron said you could furnish your happy place from memory and whimsy. When she had tried, Kirsty imagined a big room filled with items that meant something to her. She hadn’t got very far before it all fell apart.

Like a lot of Vron’s ideas, the happy place theory was barely workable. But before giving up, Kirsty had remembered to include Weezie’s magic chest of drawers, with the top drawer that always had the same thing in and the bottom drawer that never had the same thing twice and the middle drawer which was always a jumble of surprises.

There was a three-drawer chest in Jordan’s room. She was sure she had seen it. An idea clicked in her mind and a wish warmed her heart.

Kirsty went up, above Miss Teazle’s study, and looked in on her daughter.

‘Hello, Mum. What’s up?’

Jordan had her three matching pink suitcases open on the bed.

The chest of drawers was in a corner. Kirsty was drawn to it. She touched its stained surface. The brass handles were tarnished. It had taken some punishment over the years. Louise must have had a kitten; old scratches marred the bottom drawer.

(that never had the same things twice)

‘Would you mind if I had this in our room?’

‘That thing?’

‘It’s too small for your collection.’

A taller chest of thinner drawers was in the middle of the room, final resting place undecided. Its drawers were sealed with masking tape.

Jordan thought a while and Kirsty found herself on tenterhooks. What if her daughter refused? After so long without a blow-up, was this worth one?

‘Feel free, Mum.’

Kirsty was relieved and hugged Jordan, suddenly, harder than she intended.

‘Oof. What’s that for?’

‘Because I have the best family in the world.’

Jordan looked at her, not sure if she were serious or setting a trap. Kirsty couldn’t blame her, not after everything.

‘So do I, Mum.’

Tears started in Kirsty’s eyes. Happy tears.

* * *

With clothes unpacked and things provisionally arranged, Jordan could relax, easing into her room as if it were a warm, scented bath. She picked a suitable disc from a Perspex rack and fitted it into her portable CD-tape-tuner: the Chordettes, Sentimental Journey. She lowered herself into the rocking chair, gingerly in case it snapped to twigs under her weight. The chair was just her size. She settled and put out a foot, resting it against the low window-sill. She eased herself gently back and forwards, in time to ‘Carolina Moon’. The movement was strangely sexual.

Her favourite photograph of Rick was tucked into a corner of the dressing-table mirror, where he could gurn at her when she played with her face. As she rocked, his tiny eyes seemed to follow her.

When Dad and Mum told her the family was moving to the West Country, Jordan threw one of her wobbliest wobblies. She refused to eat for a week and retreated to her cupboard-like old room. Putting on her eyelashed sleep mask and earphones, she played heartbroken Patsy Cline directly to her brain.

She thought only one thing: leaving London meant losing Rick. The whole move was cunningly designed to make her utterly miserable.

It wasn’t as if coming by a boyfriend had been easy. She was one of those girls boys were afraid of. It was odd, because she had always had more boy friends than girl friends. Talking to fellas was easier because she had more to talk about with them. All the boys she had been friends with until the last few years went mad with puberty. They either started looking at her with that expression that really did have to be called ‘undisguised lust’ no matter how silly it sounded, or wanted to pour out their hearts about how they were tragically smitten with some twitty girl Jordan wouldn’t have given the time of day.

She wasn’t tribal, either: while classmates were deciding which Spice Girl to emulate, her role models were Doris Day in the tart romantic comedies of the early 1960s and Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face and Breakfast at Tiffany’s. She listened to all kinds of music, but mostly liked singers from the 1950s and early 1960s. For a while, she had worn a headband like Jackie Kennedy and dressed for college in a powder-blue suit with matching shoes and gloves. When asked why she favoured odd styles, she could only say they felt right to her, embarrassed even by terms like ‘vintage’ and ‘retro’.

The thing about Rick was that he hadn’t been at the same schools as her from the age of six. They had met in college as more-or-less adults and didn’t have any history. He noticed her in the common room, when she was smoking her third ever cigarette. She had bought a long pink holder in the Oxfam shop and had to take up the habit to make use of it. He was a sci-fi freak and said she looked like Lady Penelope from Thunderbirds. He had unmanageable red hair and crooked teeth, but she had known at once about him, as she had known at once about the Hollow.

If it had been a few years ago, the move would have meant starting all over. Tim had already forgotten his city friends and was ready for country duty. But she was different.

As soon as she saw the Hollow, she knew that moving wasn’t leaving, wasn’t a straight swap. Dad was bringing his business with him, prepared to work out of a virtual office. Mum wouldn’t cut herself off from the support network she’d built up in London. Map distance meant very little these days.

Her parents knew she had slept with Rick. She had put up with their lecture about being ‘sensible’, though she gathered that as teenagers they’d been gob-happy, pill-popping, joylessly promiscuous punks. There were photos of Mum with her hair in a Mohawk ruff. The major concession Jordan had extorted in return for her cooperation with house-hunting expeditions was that Rick would be able to sleep over at the flat. As it happens, they had only been able to take advantage of the ruling twice and on one of those times her period had been on and they couldn’t do anything. She had been assured with a solemnity on a par with a clause in a peace treaty ending a thirty-year border war that Rick would always be welcome at the Hollow, to stay for as long as he wanted. He was leaving college in a month’s time and would come down for a long visit. Then he was taking a year off to work as a cycle messenger before going to the University of the West of England in Bristol, only fifty minutes away from Sutton Mallet. It took longer to get across London in the rush hour. She was already determined to get into UWE. It made perfect sense. The Communications degree Rick was taking was ideal for her. The puzzle pieces all fitted.

She would be happy in this place. Rick too.

Back in the city, she was still a kid because everyone she knew thought of her that way. They looked at her style choices and thought she was playing dress-up, but this was the way she was, was who she was. It wasn’t going to change.

Here, at the Hollow, she would be treated as a young lady.

From her window, she saw Tim dart from tree to tree, finding spots of cover. This was his paradise too.

As she rocked, she remembered caresses. Afternoon sunlight fell upon her, warming her face and hands and throat like soft, warm fingers.

Clear voices told Jordan what she could expect from love.

* * *

Steven gave the removal men bottles of beer from the cool-box. It was a hot day and they’d unloaded in double-quick time.

The three blokes from the city, sweaty from work, sat on the grass by his drive, blinking in the sunlight. Already, he was apart from them. They were alien but he was at home. He was from the Hollow. He was a Hollow man.

‘Lovely spot you’ve found here, Steve,’ said Ben, the driver. ‘Idyllic.’

Ben’s shifters – a friendly Rasta called Trey and a silent lad, Jimmie – drank their beer and looked up at the towers. This must be totally beyond their experience.

‘Wonderful for kids,’ said Ben. ‘Specially your younger pair. Loads of places for hide and seek. They’re already at it, I see.’

‘Tim’s gone to ground,’ Steven admitted.

They looked past the house, into the orchard.

‘It’s like “how many animals can you see in this picture?”’ suggested Trey.

Steven laughed. Tim was crawling by the fallen tree, keeping close to its shrinking noontime shadow.

‘What’s your little girl’s name?’ Ben asked.

‘Jordan?’

‘No. The littler one. With the straw hat.’

‘Don’t understand your banter, old chap,’ said Steven, stiffer than he meant.

‘She was watching us inside, from the fireplace,’ said Ben. ‘Wasn’t she, lads?’

Reluctantly, Trey nodded. Steven noticed he had crossed his fingers, all eight of them.

‘Pretty little thing,’ said Ben. ‘With ribbons.’

‘Not one of mine, I’m afraid. Must be a stray.’

‘There was no girl,’ said Jimmie. He didn’t have the thin voice Steven had imagined. ‘Just shadows. Playing tricks.’

Ben let it drop. Steven was puzzled. Something was odd here, but he’d have time to hunt it down. He was going to have a lot of time.

He had arranged with his major clients to take things easy for the next month while he got the Hollow sorted out. Then, he would be open again for business and better than ever.

Steven wasn’t a stockbroker, an accountant or an investment counsellor. In the pits of the crash, ejected from the brokerage where he’d worked for most of the eighties, he had found a gap in the money market and made up his own job. He found individuals or institutions with funds to invest and brought them together with individuals or institutions with projects which needed finance. He was an intermediary, a deal-maker. It was a game, really: putting together financial jigsaws. Tatum, his personal assistant, was keeping his city office open, but the business was in Steven’s head and computer files. When he worked it out, he was surprised at how little he needed to be in London. Well over half his clients weren’t city-based. He just hoped there would be enough for Tatum to do to justify her salary. Especially when he took on someone local to handle secretary-assistant chores here.

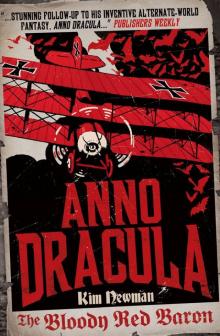

The Bloody Red Baron

The Bloody Red Baron Anno Dracula

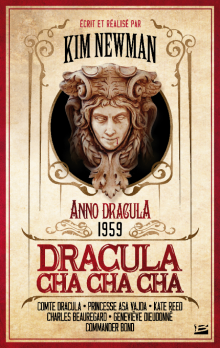

Anno Dracula Dracula Cha Cha Cha

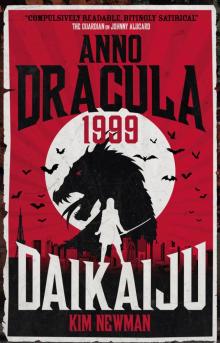

Dracula Cha Cha Cha Anno Dracula 1999

Anno Dracula 1999 Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles Angels of Music

Angels of Music The Man From the Diogenes Club

The Man From the Diogenes Club Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Night Mayor

The Night Mayor Back in the USSA

Back in the USSA Jago

Jago Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes

Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes The Quorum

The Quorum Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories

Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories Life's Lottery

Life's Lottery The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School

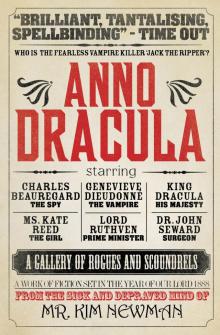

The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School Anno Dracula ad-1

Anno Dracula ad-1 The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2

The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2 An English Ghost Story

An English Ghost Story The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School

The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School The Other Side of Midnight

The Other Side of Midnight Bad Dreams

Bad Dreams Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters

Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918

The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918