- Home

- Kim Newman

Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories Page 3

Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories Read online

Page 3

I began to smile. ‘In bottles,’ I said. ‘Lined up on a druggist’s shelf. What do you call them here? Chemist’s shops. Little blue bottles, with bright yellow labels.’

‘I see you understand well enough,’ said Leo Dare, approving.

‘The formula must be highly diluted,’ said Varrable. ‘Maybe one-tenth the strength of that Jekyll used, with water…’

‘Coloured water,’ I put in.

‘…added to minimise the unpleasant side effects. I say, Quinn, why coloured?’

‘So it doesn’t look like water. Otherwise, suspicious folk think that’s all it is. I served a rough apprenticeship in a medicine show out West. The marks, ah, the customers, ignore the testimonials and the kootch dances. They open their wallets for the stuff that has the prettiest colour.’

‘Well, I never.’

‘Look to your own medicine cabinet at home. You’re an educated man, and I’ll wager you purchased your salves and cure-alls on the same basis.’

‘We’ve decided to call it a “tonic”,’ said Leo Dare.

I thought for a moment, then agreed with him. ‘The biggest hurdle will be the public perception of our product as the stuff of melodrama and murder. The name should not have associations with magic or alchemy, as would be the case with “miracle elixir” or “potion”. A “tonic” is something we all might have at home without becoming bloodthirsty monsters.’

‘From henceforth, the word “monster” is barred among us,’ decreed Leo Dare.

Mr Enfield looked down into his empty glass.

‘I concur. Though, for a tiny fraction of our customership, the attraction will all be wrapped up in the business of Jekyll and Hyde. Some souls have a temptation to sample the dark depths. We should be aware of that and fashion strategies to pull in that segment without alienating the greater public, whose interest will be chiefly, ah, cosmetic. Everyone above a certain age wishes to look younger, to feel younger.’

‘Indeed. And we offer a tonic that will let them be younger.’

‘We should be cautious, Mr Dare,’ said Varrable. ‘The formula must be carefully tested. Its effects are, as yet, unpredictable.’

‘Indeed. Indeed. But it is also vital, Dr Varrable, that we consider the practicalities. I have asked Quinn to apply his wits to matters outside your laboratory. Many considerations must be made before Jekyll Tonic can be presented to the public.’

‘What of the legalities?’ I asked. ‘Aren’t there stringent rules and regulations? Government boards about medicines and poisons?’

‘There certainly are, and Sir Marmaduke sits on them all.’

Sir Marmaduke grunted again and made a speech.

‘It is not the place of this house to stand in the way of progress, sirrah. The law should not interpose itself between a thing that is desired and the people who desire it. That has always been my philosophy and it should be ever the philosophy of this government. If Jekyll Tonic, this wondrous boon to all humanity, were to be denied us because of the sorry fate of one researcher, where would frivolous, anti-medicinal legislation cease? Would sufferers from toothache be prevented from seeking the solace of such perfectly harmless, widely used balms as laudanum, cocaine and heroin? I pity anyone who persists in needless pain because the dusty senior fatheads of the medical profession, who earned their doctorates in the days of body-snatching and leeches, insist on tying every new discovery up in committees of inquiry into the committees of inquiry, of over-regulating and hamstringing our valiant and clear-sighted experimental pioneers.

‘The present manufacturers have taken to heart the lesson of Dr Jekyll, and have gone to great lengths to remove from his formula the impurities that robbed him of his mind even as it gave him strength of body and constitution. Jekyll Tonic is a different matter now that it has been improved and perfected. Its effects are purely beneficial, purely physical. I myself shall ensure that all the members of my household take one tablespoonful of Jekyll Tonic daily and am confident that there will be no ill effects. This parliament must declare for Jekyll Tonic, and decisively, lest the health of the nation be sapped, and our overseas competitors draw ahead.’

Mr Enfield clapped satirically. Sir Marmaduke bowed gravely to him.

‘Think of the enormous benefit it will be for the poor,’ said Lady Knowe. ‘Always think of the poor.’

‘Jekyll Tonic will retail at threepence, but we intend to put out an extremely diluted version in a smaller bottle at a halfpenny a bottle,’ said Leo Dare.

‘For paupers and children,’ explained Sir Marmaduke.

I began to do summations in my head. Leo Dare gave figures.

‘A farthing for the bottle, the cork and the gummed label; a quarter-farthing for the Tonic itself…’

‘That little?’

‘In bulk, yes. I have cornered the uncommon elements. The rest is just water and sugar for the taste.’

‘More than twopence halfpenny sheer profit?’

‘We expect demand to be enormous, Quinn. Especially after you have worked your own brand of alchemy.’

This put galvanic girdles in the ashcan.

‘One thing,’ I said. ‘What does the Tonic actually do?’

‘I suppose someone had to ask that question, Quinn. What does the Jekyll Tonic actually do? Let us try an experiment.’

He raised the glass of what I had taken for port, looked at the clear pink-orange fluid, touched the rim to his lower lip, then inclined his head backwards. He took in the glassful at a gulp and swallowed it at once.

Shadows crept across his face.

But it was only the firelight.

‘Most refreshing. I can assure you, as I’ll be willing to attest before lawyers, that I feel enormously invigorated and that my senses are sharper by several degrees of magnitude. The outward effect made famous by Dr Jekyll is only notable after a course of tonics, and then only in the cases of those who most desire a change of appearance. I myself am happy with the way I look.’

I understood perfectly. I had been in the snake-oil business before.

But never with the Jekyll name.

I foresaw rooms full of gold, profits pouring in like cataracts, fortunes made for all of us.

* * *

Varrable’s ‘laboratory’ was a former stables in Shoreditch. Leo Dare had lately purchased Mercury Carriages, a hansom cab concern, not in order to run the operation (whose slogan was an uninspiring ‘Fleet and Economical’) but to close it down. A sudden surge in demand for quality horsemeat in Northern France made it more profitable to despatch Dobbin to the knackers than to retain the nag in harness.

Leo Dare had come to an arrangement with several long-established businesses with a combined interest in the hackney carriage trade (their more pleasing slogan, ‘Hansom is as Hansom Does!’), pledging to eliminate a rogue firm given to undercutting the fares of bigger rivals in return for a substantial honorarium and a percentage of increased profits over a period of five years. Had the cab combine turned him away, he would doubtless have reduced Mercury fares to a laughable minimum and brought about a complete catastrophe in the carriage business, taking his profit from subsidiary concerns. The Mercury premises were at his disposal, and now served as a convenient headquarters for the developmental work of the Jekyll Tonic consortium.

Our research was carried out in such secrecy that no sign outside the works marked our presence. On this first visit, I found the address only by the sheerest chance. I noticed a thin crowd of shifty-looking fellows in heavy coats and scarves loitering on a corner. From the long buggy-whips several of them were toting, I gathered that these were freshly unemployed cabbies, mindlessly haunting their former base of operations. Mercury Carriages had tended to draw their drivers from a pool of swarthy immigrants from the Mediterranean countries, and so I noted not a few fezzes among the traditional flat caps. A couple of big bruisers in billycock hats guarded the stable doors, with cudgels to hand, as a precaution against an invasion of these disgruntled cast-offs.

My own carriage, a sleek four-horse job retained permanently at my disposal by Leo Dare through another clause in his agreement with the cab trust, drew up outside the stables, exciting mutters of discontent from the corner louts. I got out, told the liveried coachman to await my convenience, and presented my credentials to the bruiser who looked most capable of coherent thought.

‘Yer on the list, Mr Quinn,’ I was told.

A regular-sized door cut into the large stable doors was hauled open and I stepped into a doubly malodorous place. Doubly, for its former usage was memorialised by the trodden-in dung of equines (currently gracing the plates of provincial French gourmands, I trusted), while its current occupation was most pungently signalled by the stench of chemical processes. I wrapped a handkerchief around my nose and mouth, which gave me the look of a desperado robbing a stagecoach. My eyes still watered.

If you think of a laboratory, you doubtless form a mental picture of tables supporting contraptions of glass tubes, beakers and retorts, with flames at strategic places. Coloured liquids bubble and ferment, while strange heavy smoke pours from funnel-shaped tube mouths. Perhaps one wall is given over to cages for the animals – rats, rabbits, monkeys – used in experimentation, and in a corner is an arrangement of galvanic batteries, bottles of acid, switches, levers and metallic spheres a-crackle with the bluish light of harnessed lightning.

This was a former stables. With open barrels of smelly gloop.

Hugo Varrable, in a much-stained apron and shirtsleeves, stirred a vat with a long stick. He wore a canvas bucket on his head. It looked like a giant dirty thumb stuck out of his collar, with an isinglass faceplate for a nail.

‘It’s all done, Billy,’ said Varrable, voice a mumble inside the bucket. He turned from the vat to pick up a stoppered flask of the now-familiar fluid. ‘Come on through.’

He led me out of the stables into a courtyard where the fleet of Mercury cabs, stripped of brass fittings and iron wheel rims, sat decaying slowly to firewood. Leo Dare would profit from that come winter.

‘Have our volunteers appeared?’ I asked.

Varrable took off his bucket and coughed. ‘Some of them.’

‘Only some?’

Varrable shrugged. ‘The Jekyll name may have given one or two second thoughts about participating in the experiment.’

‘Indeed.’

Awaiting us in what had once been the common room of the cabbies were three lank-haired, languid individuals, students who fancied themselves ornaments to the aesthetic movement. One of the species was a young woman, though she wore the same cut of velvet breeches and jacket as her fellows. They had been exchanging bored, nasal witticisms. At our entrance, they perked up. Beneath their habitual posing, they were skittish. All considered, apprehension was understandable.

‘This won’t do, Doc,’ I said, alarming our volunteers. ‘The effect of the Tonic we want to push the most is rejuvenation. These exquisites are sickeningly youthful enough as it is.’

‘There are other effects, measurable upon all subjects.’

‘Yes, yes. But our “selling point” is the youth angle. Are you telling me you could find no elderly or infirm person willing to take part in the testing of our medical miracle?’

‘We put the word out at an art school. All the patent medicine concerns do the same.’

‘There’s your problem, Doc. However, it’s easily set right. If you’ll excuse me for a moment.’

I stepped out of the common room and went round to the main gates. The bruisers let me pass and I crossed the road. The loitering ex-cabbies edged away from me with suspicion. Among the Turkish brigands and Greek cutthroats, I found several English individuals of advanced age, faces weathered from exposure to the elements, backs and limbs bent by years spent hunched at the top of a cab, breath wheezy from breathing in gallons of London pea soup.

‘Who among you would care to earn a shilling?’ I asked.

* * *

Varrable worked the results up into a learned paper no one actually read. Leo Dare arranged for its publication in an academic journal whose name eventually lent weight to our campaign. When The Lancet, alarmed by the spectres of Jekyll and Hyde, ran an editorial against us, thunderous voices among the medical profession – not to mention Sir Marmaduke Collynge – were raised against the brand of irresponsible trade journalism that inveighs against a perfectly legal product, which has yet to be judged either way by the final arbiters of such matters. ‘The public shall make up its own mind,’ said Sir Marmaduke, at every opportunity, ‘for it always does, the average fellow being far more astute than your addle-brained quack, consumed with envy of the achievements of younger, more free-thinking men.’

As the brewing and refining continued in Shoreditch, Leo Dare took the elementary precaution of establishing, through Lady Knowe, a philanthropic trust to dispense grants supporting avenues of medical inquiry whose pursuit was blocked by the hidebound bodies responsible for the allocation of funds at the country’s major universities, medical schools and teaching hospitals. This enabled many a hobby horse to be ridden and pet project to be nurtured, doubtless contributing (in the long run) to the health of the nation and the wealth of scientific knowledge. A correlation of this generosity was that researchers who benefited from the foundation’s beneficence were predisposed to uphold the reputation of the late Dr Henry Jekyll on the public podium and give testimony that his work, though unfortunately applied in the first instance, was perfectly sound. These worthies tended to have passionate beliefs in the benefits of naturism, monkey glands, cosmetic amputation, the consumption of one’s own water, phrenology, galvanic stimulation (our old friend), vegetarianism and other medical tangentia. However, their MDs were every jot as legit as those of the head surgeon at Barts or the Queen’s own physician, and the public (perhaps regrettably) tends to think one doctor as good as another when reading a testimonial.

Having observed the experiment firsthand, I did not quite become a fanatic believer in Jekyll Tonic. However, I had to concede that it was a very superior species of snake oil.

For a start, its effects were immediate and visible.

Our would-be poets and unemployed cabbies did not transform into a pack of Neanderthal men and take to battering their fellows with makeshift clubs, but several evinced genuine transformations of feature and form. A very bald fellow instantly sprouted flowing locks that were the envy of the decadents in the room, suggesting we could market the Tonic as a hair restorer (always a popular line). Arthritic fists, all knuckles from a lifetime of gripping reins, opened into strong, young hands. A shy stammerer among the students was suddenly able to pour forth a flood of impromptu rhyming and would not shut up for two days, when the effect suddenly (and mercifully, for his circle) wore off. Another poet, an avowed anarchist and shamer of convention, rushed from the stables, eluding our guards, hacking at his hair with a penknife. He was later found to have taken a position as a junior clerk with a respectable firm of solicitors, which he quit suddenly as his old personality resurfaced.

Varrable remained concerned that the effects of the Tonic were essentially unpredictable, as proved by further experimentation with a range of volunteers from wider strata of society. We thought we should have to pay substantial ‘hush money’ to a curate who sampled Jekyll Tonic and passed through a bizarre hermaphrodite stage to emerge (briefly) as a woman of exceedingly low character with an unhealthy interest in the gallants of Britannia’s Navy. Leo Dare overruled our request for cash, predicting (correctly) that the cleric in question would rather bribe us to keep from his bishop any word of the Portsmouth adventures of his female alter ego.

None of our volunteers killed anyone, which was a great relief.

Only the anarchist and the curate vowed never to repeat the experience. I had a sense that the cleric came reluctantly to the decision and would eventually alter it, perhaps making surreptitious purchase of the Tonic once it was generally available and indulging in its use only after taking

precautions in the name of discretion. The others returned, bringing with them sundry family members and friends. They all clamoured for the Tonic in a manner that suggested Leo Dare had another ‘winner’ on his hands.

The Hon. Hilary Belligo, the stammering aesthete, splutteringly conveyed to us that he would be prepared to forego the shilling remuneration we offered for participation in the experiment and would meet any price we suggested if an inexhaustible supply of the Tonic were made available to him.

Varrable and I independently liquidated all our other holdings and ploughed our money into the consortium stock issue. The next day, before any public announcement had been made, the value of our shares tripled.

I drew the line at sampling the formula myself. If called, I was only too happy to swallow a few ounces of coloured water – doubtless the same recipe Leo Dare had theatrically quaffed at our first meeting – and declare myself satisfyingly rejuvenated.

Varrable formed a theory that the effect of the Tonic was to reshape each individual into the person they secretly wanted to be. The ageing, stuffy Jekyll had become the young libertine Hyde; but, as the name suggests, the violent thug had always been ‘hiding’ inside the respectable man. Sometimes, as perhaps with Jekyll and certainly with our anarchist and our curate, the transformations proved a shock to the subjects because the Tonic was no respecter of hypocrisy. It acted on secret wishes, some concealed even from those who harboured them. Many were unaware of the fierceness that burned in their breasts, the need to be somebody else. My own reluctance to take the Tonic came from an unanswered question: I thought that I was perfectly happy to be myself, but what if I was wrong? What if some notion I couldn’t consciously recall was stuck there? As a lad, I wanted to be a pirate when I grew up. Would a course of Jekyll Tonic have made me grow an eyepatch and a pegleg? Might I not have come to myself, like that sore curate in a Portsmouth grog-house, to find I had taken the Queen’s shilling and was miles out to sea on a ship of the line?

* * *

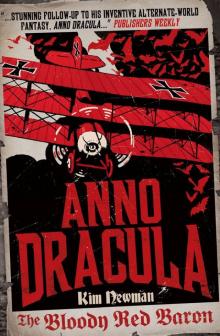

The Bloody Red Baron

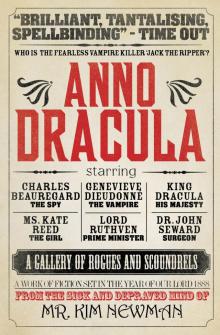

The Bloody Red Baron Anno Dracula

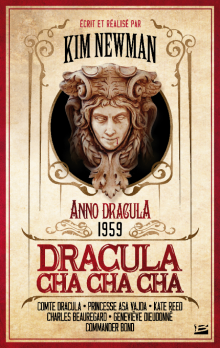

Anno Dracula Dracula Cha Cha Cha

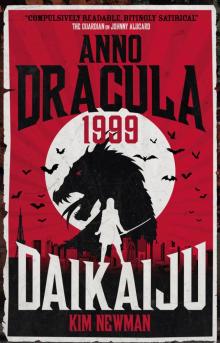

Dracula Cha Cha Cha Anno Dracula 1999

Anno Dracula 1999 Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles Angels of Music

Angels of Music The Man From the Diogenes Club

The Man From the Diogenes Club Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Night Mayor

The Night Mayor Back in the USSA

Back in the USSA Jago

Jago Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes

Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes The Quorum

The Quorum Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories

Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories Life's Lottery

Life's Lottery The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School

The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School Anno Dracula ad-1

Anno Dracula ad-1 The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2

The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2 An English Ghost Story

An English Ghost Story The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School

The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School The Other Side of Midnight

The Other Side of Midnight Bad Dreams

Bad Dreams Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters

Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918

The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918