- Home

- Kim Newman

The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School Page 2

The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School Read online

Page 2

Using the banister, she pulled herself hand over hand. Trying not to think about going against nature, Amy glided upwards, toes barely brushing the steps. When she reached the first-storey landing, her usual weight settled back. Her shoes were set down on the carpet. After her floats, she felt heavy, as if Newton himself were paying her back for contravening his Law of Gravity.

A large door bore an engraved brass plate.

Dr Myrna Swan, Headmistress

D. Phil. (Bangalore), D. Eng (Sao Paolo), M. Script. (Wells

Cathedral) & Cetera.

Amy raised a knuckle. A voice came from beyond before she could rap on the door.

‘Enter, Thomsett.’

The door opened by itself. Across the book-lined room, a slim, imposing woman of indeterminate age sat behind a lacquer-topped desk.

Amy’s hand was still up, where the door wasn’t.

‘You didn’t do that,’ said Headmistress. ‘I did. I am not in the habit of issuing invitations twice.’

Amy stepped into the room.

Headmistress worked a lever on an apparatus like a typewriter mated with a sewing machine. The door closed behind Amy.

Above the contraption were several copper tubes which ended in eyepieces. Dr Swan had been looking through one. Another tube, with a lens, was out on the landing. It must be an array of mirrors, like a triple-jointed periscope.

Had Headmistress seen her flying? Not that it was really flying. Just – fast floating.

Dr Swan’s jet-black hair was coiffured in a bun on top of her head, with two pearl-tipped needles stuck through it. Her face was white but for red, bee-stung lips and a black beauty mark. Tiny lines showed around her large green-gold eyes. Amy remembered what Frecks said about the fluence. Dr Swan appeared over and over in the pictures downstairs. She had taken office in the founding year. Girls grew up and left, but she stayed the same, always dead centre in the school photograph. Her age must be even more indeterminate than it seemed.

Her tight silk dress was like a long tunic, green with gold griffin designs. A nurse’s watch was pinned like a brooch on her breast. Her black academic gown hung loosely. It had sawtooth trailing edges and a flaring demon-king collar.

‘Thomsett, Amanda,’ said Dr Swan, tapping a folder on her desk. ‘Third, Desdemona, Unusual.’

Amy understood half of that.

‘Desdemona is your House,’ Headmistress explained. ‘Drearcliff has five. Ariel, Viola, Tamora, Desdemona and Goneril. Had you arrived at the beginning of year, you would be Ariel. In the circumstance, you fit where you must. Desdemona was down a girl. As for Unusual… your mother wrote about “incidents” at home. Footprints on the ceiling. She trusts you will grow out of it…’

Amy blushed like a fire engine.

‘I know you will not,’ said Dr Swan. ‘Unusuals have Abilities or Attributes, sometimes both. You are blessed with Abilities. It is our responsibility to help you cultivate them, to find Applications.’

Amy was astonished. This was not what she – or Mother! – expected from her new school. In the months since she first came unstuck from the ground, Amy had been subjected to cold baths, weighted pinafores, long walks, hobbling boots and a buzzing, tickling electric belt. Leeches and exorcism were on the cards. Mother’s whole idea in sending Amy to Drearcliff was to clamp down on floating.

‘We have a tradition of Unusual Girls at Drearcliff. I like to think of them as my cygnets. You’ve heard of Lucinda Tregellis-d’Aulney…’

The Aviatrix. Britain’s flying heroine. The only woman among the Splendid Six, Britain’s most unique and remarkable defenders. She didn’t just float, she soared. Amy followed her exploits in Girls’ Paper. Lady Lucinda was currently prominent in the illustrated press for nabbing Jimmy O’Goblins. The coinernecromancer, whose lightweight sovereigns caused escalating misfortune each time they were spent, was in the Special Prison with a sore head. The Aviatrix was invited to high tea at the Palace with the King and the governor of the Bank of England.

‘Tregellis-d’Aulney passed out in ’16. She has made a name for herself. So have other Drearcliff Unusuals. Irene Dobson, the medium. Cressida Hervey, the Australian opal millionairess – with dowsing abilities. Monica Bright – ‘Shiner’ Bright of the Women’s Auxiliary Police. Grace Ki, the Ghost Lantern Girl. Urania Strangways, who survived hanging in Montevideo last year. Luna Bartendale, the psychic investigator. I take pride in my cygnets’ achievements, whichever direction their enthusiasms take them. You have, I trust, an enthusiasm?’

Shyly, Amy admitted ‘I like moths. Not collecting them. I don’t believe in killing jars and pins. I’ve sketched three hundred and twelve distinct live specimens. British Isles, of course. I’m nowhere near finished. There are over two thousand British moth species alone.’

‘That is not what I mean by an enthusiasm, Thomsett. Still, it’s early days yet. Can you, ah…?’

Dr Swan gestured with her flat palm, lifting it up over her desk.

Amy looked at her toes. She worked so desperately not to float, she couldn’t unclench whatever it was that held her to the ground.

She strained, eyes shut, making noises inside her head.

‘You are trying too hard, Thomsett. Nothing good comes of that. You must let go, not hold tight.’

Amy nodded and relaxed. She rose an inch or so from the floor, but couldn’t stay up. She clumped down again.

Dr Swan raised an eyebrow. ‘Promising.’

Amy was exhausted. Had the Aviatrix – who grew temporary wings of ectoplasm – started like this? With tiny floats? Did she ever wake up thumping against her ceiling, blinded by sheets tented around her, in a panic that the world had gone topsy-turvy?

‘And the other thing,’ Headmistress said. She put a fountain pen on her blotter.

Amy thought about the pen floating, but it only wobbled – and leaked a bit.

She tried to apologise. She could sometimes make things float. More often, she gave herself a nosebleed. Frankly, it was easy enough to pick up a pen with her fingers. Taking hold of things with her mind was a strain.

Dr Swan didn’t press her further.

‘My eye will be always on you,’ said Headmistress, tapping her copper tubes. ‘We shall see what can be done with your Abilities. Pick up your Time-Table Book from Keys.’

Amy knew who Headmistress meant.

‘Dismissed,’ said Dr Swan, depressing a lever.

The door opened. Amy backed through it.

III: Dorm Three

OUTSIDE OLD HOUSE, Amy found four Seconds performing an intricate skipping ritual to a never-ending rhyme about drowned black babies in a terrible flood. She asked where she could find Dorm Three. They stopped in mid-chant, staring as if she were a person from Porlock – as it happens, only a few miles away – interrupting Coleridge in full poetical flow. The solemn adjudicator pointed up at the top of Old House, then crossed herself and snapped her fingers to order resumption of skipping and chanting. The terrible flood had to drown many more black babies.

Inside the building, which smelled of rain on rocks, Amy found a tree of signs pointing to destinations as diverse as ‘Refectory’, ‘Stamp Club’, ‘Timbuctoo’ and ‘Nurse’. A broken-necked Mr Punch dangled from the Nurse sign in a hangman’s noose, pricking Amy’s fears for Roly Pontoons. Higher branches indicated dorms were on the upper floors.

Amy climbed a winding stone staircase. Names, phrases and dates were scratched into the walls. At her old school, boarders slept in something like a hospital ward or a barracks – a big room with beds lined up opposite each other. At Drearcliff, dorms were long, dark corridors with doors off to either side. Amy didn’t know where to go from the landing, so she opened the first door. Four beds fit into a room the size of the one Lettie the maid lived in at home. A girl with two sets of extra-thick spectacles – one in her hair like an Alice band – was putting together a tiny guillotine from lolly-sticks and a safety razor-blade.

‘You want Frecks’ cell,’ she

said, without looking up from her labours. ‘End of the line, new bug. You’ll whiff it before you see it. No mistaking Kali’s herbal fags. Now, push off will you… this little beast has to be in chopping order tomorrow or I’m for a roasting from Digger Downs.’

Amy ventured on. From behind a closed door, she heard a quid pro quo Latin quiz. She caught a peculiar fragrance – heady, a little exhilarating – wafting from an open room at the far end of the corridor.

Sticking her head in, she found Frecks lolled on a cot, perusing a volume with a brown paper cover. She looked up.

‘My Nine Nights in a Harem,’ Frecks explained. ‘Fearful rot. Come the deuce in, Thomsett. Meet your fellow dwellers in despair.’

Amy stepped into the cell, ducking to avoid bumping her head on the low lintel. She wouldn’t have much room to float here.

‘Thomsett, this is Light Fingers…’

A small, blonde girl sat in a rocking chair, deftly embroidering a piece of muslin. She held it up to her face. It was a Columbine mask, with fine stitching around eye- and mouth-holes. Little sequin tears sparkled on one cheek.

‘The fuming reprobate is Princess Kali.’

A slender brown girl with a red forehead dot and a gold snail stuck to her nose sat on a mat, legs folded under her. She puffed a slim cigarette in a long holder as if it were a religious obligation. Her eyes were slightly glazed.

‘Me, you know,’ said Frecks. ‘That’s your corner.’

Frecks indicated a neatly made, if somewhat forlorn, miniature bed. A dagger was stuck through the pillow.

‘Don’t mind the pig-sticker,’ said Frecks. ‘It’s not for you. Was sent to the last girl before she took poorly. Never did get to the bottom of that ’un. Many were the questions about dear departed Imogen Ames.’

Light Fingers set aside her needlework.

‘She’s quick,’ said Frecks. ‘Her register name is Emma Naisbitt. Her parents are in jail. Which puts her one up on most of us. We tend to be orphans or semi-orphans at Drearcliff. My lot were shot as spies in the War. By the Hun, I hasten to add. All very glamorous and tragic. I was packed off here by my brother. Lord Ralph holds the purse strings till I’m eighteen and past it. Worse luck, since he’s a gambling fool and a fathead for the fillies. I fully expect him to run through the dosh and leave me to make a way in the world by wits alone. He’s tragic, but not very glamorous. Still, I don’t have the worst of it in this cell. Kali’s Pa had her Ma put to death for displeasing him. He’s a bandit rajah in far-off Kafiristan. He’s run through dozens of wives.’

Kali rose elegantly, hands pressed together as if in prayer, and stood on one leg like a flamingo. She had masses of very black hair.

‘Hya, dollface,’ said the Hindu girl, rather musically. ‘Whaddaya know, whaddaya say?’

‘Kali learned English from American magazines,’ Frecks footnoted.

‘Ahhh, nertz! I talks good as any other dame in the joint.’

Kali put both feet on the floor and stubbed out her cigarette in a saucer. She had pictures from the rotogravure pinned up over her cot – scowling men in hats: Lon Chaney, Al Capone, Jack Dempsey.

‘I forgot to ask,’ said Frecks. ‘Are you down one parent or two?’

‘One,’ said Amy. ‘My father. The War.’

‘Tough break, kiddo,’ said Kali.

‘Say no more,’ said Frecks. ‘Mystery lingers, though. Why’ve you suddenly been sent here? In the middle of autumn term? There’s usually no mistake about whether one is or is not Drearcliff material. Born with a caul, font bubbling over at baptism, nannies fleeing with hair gone white overnight, scratches on the nursery wallpaper…’

Amy hesitated. Interest sparked. Frecks and Kali exchanged a Significant Look.

‘Light Fingers,’ said Frecks. ‘You’ve got competition. We have another Unusual.’

Denial sprung up in Amy’s throat, but died. There was no point. It was out before she was properly here. Mother would be livid.

Light Fingers regarded Amy with suspicion, tilting her head to one side and then the other.

‘It’s not something you can see,’ said Frecks. ‘Like Gould of the Fourth and her teeth and nails. Or that Goneril guppy with gills. It’s something she does. Hope you’re not a mind reader, Thomsett. They’re unpopular, for reasons obvious. Dearly departed Ames was a brain-peeper. Didn’t make her happy.’

Amy was tight inside. Close to tears, though she kept them in.

‘There there, child,’ said Frecks. ‘We won’t hurt. Tell all.’

‘C’mon, doll, cough it up an’ ya’ll feel better.’

The three girls were close to her now. Amy knew this was important.

‘Light Fingers,’ said Frecks, ‘show her yours.’

The blonde girl reached out and tapped Amy on the chest with her right forefinger, then opened her left hand to show a black-headed tiepin.

Amy, astonished, touched her tie. The pin was missing.

‘How…?’

‘Prestidigitation, old thing,’ said Frecks. ‘As practised in the Halls by respected conjurers. And in the stalls by disreputable pickpockets. The hand is quicker than the eye. Naisbitt’s hands are quicker than a hummingbird’s wings.’

Light Fingers clapped her hands and showed empty palms. Amy found her pin back in place. A bead of blood stood out on the girl’s forefinger. Light Fingers licked the tiny wound.

‘Gets it from her parents. They had an act at the Tivoli. Doves out of hats. Escapes from water-tanks. Also, a profitable sideline: lifting sparklers from nobs in the audience. Got caught at it. Hence, jail. Captain Rattray nabbed ’em. You know, Blackfist. The big bruiser in the Splendid Six – with the Blue Streak, Lord Piltdown, the Aviatrix and the other two no one remembers. Mrs Naisbitt made a pass for Rattray’s magic gem. That was the end of that.’

Amy knew all about Blackfist. Dennis Rattray, a gentleman explorer, had discovered a pre-human cyclopean idol in a cavern temple under the Andes. From its forehead, he plucked the famous Fang of Night jewel. The story was that when he made a fist around the mystic purple-black gemstone, his body became as impervious to harm as granite and his blows landed with the force of a wrecking-ball. Since then, he had biffed rotters and foiled plots against the Empire. He also concerned himself with less momentous, nevertheless baffling crimes… such as, presumably, the Naisbitts’ pilfering spree.

‘Mum and Dad could escape any time they want,’ said Light Fingers. ‘They get out of their prisons and visit each other. All the time. But they go back for the head-counts. Less trouble in the long run. They only stole from horrid people, by the way… quite a lot of rich people are horrid. And Rattray said he’d let them off if Mum went to Brighton with him for a Bank Holiday weekend, so he’s fairly horrid himself, no matter what the papers say. After all, he got to be Blackfist by stealing something which was perfectly happy where it was and has the nerve to pinch other folks who are just trying to make a living.’

‘Editorial comment over,’ said Frecks.

Amy assumed Light Fingers was biased, but what she said sounded likely. It had always seemed to her that Blackfist enjoyed biffing rotters rather more than was entirely healthy. There was once talk of the Aviatrix and Blackfist getting engaged, but that cooled down… and no wonder, if he was the sort to issue improper invitations to married lady thieves.

The three girls looked at Amy, expectant.

‘A shy one,’ said Frecks. ‘Probably taught to hide her light under a bushel. We haven’t anything else to show. Kali and I aren’t Unusual that way. Just warped. Drearcliff Girls have something extra or something missing. Not just parents. Bits got left out when we were put together. Know what Kali’s going to do to dear old Dad when she goes home?’

Kali drew her thumbnail across her throat and made a ‘krkkkk’ sound.

‘Concrete overshoes, wooden waistcoat… curtains, kiddo!’

‘Means it, too. She’s going to be a bandit queen. She’s already coloured in her territory on the

map. So, Thomsett, give…’

It wasn’t that easy. In Headmistress’s study, she hadn’t been able to perform on cue. Not really. It would be the same here.

‘She is giving,’ said Light Fingers, ‘look…!’

Amy was surprised, then glanced down. She was a full six inches off the floor, feet dangling limp. Her head pressed the plastered ceiling.

Kali and Frecks were wide-eyed. Light Fingers looked a little frightened.

Frecks whistled, long and shrill.

‘That was an appropriate whistle,’ she explained. ‘Crivens, you’re a pixie!’

Amy went inside herself, and thought heavy thoughts. She came down gently, on toepoints, then settled on her heels.

‘I am not a pixie,’ she said.

‘But you can fly!’

She shook her head. ‘No, I can’t fly. I can float. It’s not the same.’

The Aviatrix could fly. She could flap her wings, zoom along, bank and roll, ascend and descend, outpace any land craft. Amy could wave her arms all she wanted, but just went up and up like a balloon. So far, she’d only floated deliberately indoors. Once, she had dozed under a tree like Alice and woke up trapped by low branches. Mother said if she didn’t stop it, she’d drift away and be lost in the clouds.

‘Still, you’re an Unusual,’ said Frecks. ‘Headmistress must love you.’

Kali snarled. ‘Stay away from Swan! She’s trouble in velvet! A regular cyanide mama!’

‘Tell you what, though,’ said Frecks. ‘Desdemona won’t come bottom in netball this term. Not with two Unusuals. Light Fingers can steal the ball and make an invisible pass. Thomsett can float and pop it through the hoop from above. A tough rind for the harpies of Goneril to chew. Must get ten shillings down with Nellie Pugh in the kitchens – she’s school bookie, don’t you know? – before word gets out.’

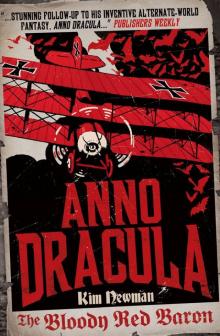

The Bloody Red Baron

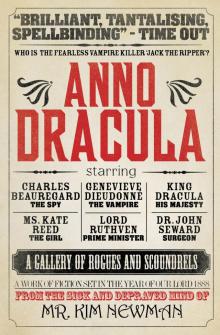

The Bloody Red Baron Anno Dracula

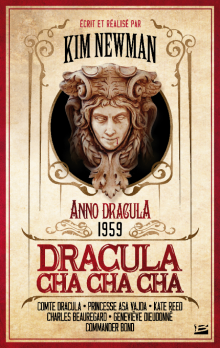

Anno Dracula Dracula Cha Cha Cha

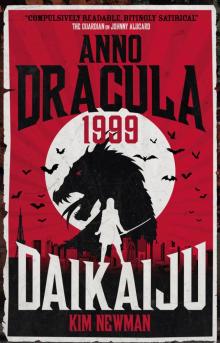

Dracula Cha Cha Cha Anno Dracula 1999

Anno Dracula 1999 Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles Angels of Music

Angels of Music The Man From the Diogenes Club

The Man From the Diogenes Club Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Night Mayor

The Night Mayor Back in the USSA

Back in the USSA Jago

Jago Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes

Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes The Quorum

The Quorum Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories

Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories Life's Lottery

Life's Lottery The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School

The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School Anno Dracula ad-1

Anno Dracula ad-1 The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2

The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2 An English Ghost Story

An English Ghost Story The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School

The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School The Other Side of Midnight

The Other Side of Midnight Bad Dreams

Bad Dreams Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters

Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918

The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918