- Home

- Kim Newman

An English Ghost Story Page 11

An English Ghost Story Read online

Page 11

He replied to Tatum, telling her to bring the client to shore and call him in for a lightning deal-clinch when she had landed him. Should he ask her to check on Precious Rick? No, that was well beyond her remit.

Ten minutes later, as he was marking up an investment prospectus he distrusted more with each glossy fold-out, his screensaver cut in. A single green word slid across the black.

CAREFUL.

He looked again and the word was just a software logo.

It might have been in his mind, but was good advice nevertheless.

* * *

The MP had been reading him the little books by the lady who had lived at the Hollow before them. They had seemed nonessential at first, but Tim now recognised vital intel. The stories, which were about a creepy little girl called Weezie, contained a wealth of coded reference points.

It was strange to hear something from an old book and know the exact tree it came from. Weezie had a hidey-hole in Green Base, too, and also received tributes from the IP, whom she called ghosts. Features of the land and the house turned up in the stories. Almost every piece of furniture or corner of the Hollow had been fitted into the books somehow, as if the lady were leaving messages for him.

Had the Weezie woman given him the U-Dub?

He listened carefully to each story, sensitive to coded orders. The MP didn’t understand half of what she was passing on, but that was the point of cipher.

The story finished and Mum shut the book.

He gathered the MP had read to Jordan when she was littler than he was now. But she’d never read to him until the Hollow. This was part of their lives now. Routine, SOP – a comfort.

‘Is Jordan going to London?’

‘No, Tim,’ said the MP. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘She had her London face on tonight.’

The MP thought a moment. ‘Yes, I suppose she did. It’s just a mood. We all have them in this family. More than most people, I should say.’

‘But it’s different here.’

‘Better. Yes. Jordan will be her new self again.’

‘When?’

‘Soon, I’m sure. Have you brushed your teeth?’

‘Yes, ma’am.’

‘Good night then.’

The MP withdrew. He heard her going down the twisted tower staircase to her own room.

Tim stretched out in his bed, lying flat but to attention. The U-Dub was under his pillow, as close to hand always as the football, the case of launch codes that went everywhere with the American President. A smooth pebble was nocked and ready, in readiness for the first report of hostile activity.

He turned his mind to tonight’s story, Weezie and the Dancing Stones, and tried to puzzle out his orders. He thought he was to hold fast and make no sudden moves.

Sleep crept over him.

* * *

In the dark, in her dark, Jordan was cold with fury. She knew she should be concerned. It was possible, likely even, that Rick had only been killed in a traffic accident. But she’d grown beyond that worry. She knew this was the worst-case scenario. He just plain hadn’t come.

(That’s what he thought of her, she was worthless.)

She thought back, replaying each of their conversations, in person before the move, by phone after. She realised she had worked everything out and Rick had done no more than give silent assent. He never contradicted, never said anything wouldn’t be possible, that he wasn’t interested or had other commitments. She had even picked the date for his visit. He’d had no opinion, never contributed to the plan she’d formulated.

That was the most despicable thing. At any time, he could have spoken up. He could have said no. There would have been fireworks, but it would have been honest.

Instead, he had done the easiest thing. He’d let her leave the city, let her witter on about the future, and gone about the quiet, vicious business of forgetting her.

(He could be dead in a ditch, corpse trapped in a crumpled car.)

No. He was back home, with his Dad cooking his tea and Walker goading him about Spock ears.

Rick was content to lean back and let other people fix things for him, giving a silent nod to carefully worked-through plans he was then somehow not quite able to carry out. In his gang, Walker had all the ideas (bad ones, usually). With her, Rick was plasticine. He went along with whatever she said but didn’t contribute anything really. He would nod agreement but not lift a finger. If you sent five people to different shops to gather the ingredients for an omelette, Rick would be the one who forgot eggs and came back with a plastic dinosaur with flashing lights in its eyes.

Was anyone else involved in the betrayal?

(The Wild Witch, Veronica.)

Ghastly, impossible. She was old enough to be…

Old, anyway. It was hard to tell with Veronica.

She reeled in that line of thought.

Blaming the Wild Witch for everything that had happened to the family, from Tim’s bout of whooping cough to the failure of Mum’s businesses, was too easy. Veronica’s ‘homoeopathic remedies’ never worked and she was useless as representative-at-large for Oddments. But she was just a grown-up looney. Not Dracula in a dress.

This wasn’t about the Wild Witch. This was about Rick.

(This was about Jordan.)

She put one last CD into her player, pulling her headphones on like a helmet. She injected Lesley Gore into her brain: ‘It’s My Party’.

Carrying the CD player like Red Riding Hood’s basket, she left her room, went downstairs and stepped through the unlocked kitchen door into the orchard. There was no moon and no light from the house, but the needle-points of stars glinted above, four hundred million jabs of venom. She looked across the moor. There was a dark shimmer to the wet fields, as if something under the ground were stirring in sleep.

Tears wet her cheeks, but she didn’t sob. It was just her eyes leaking.

The Lesley Gore of ‘It’s My Party’ was hysterical, crying from shock. That wasn’t Jordan’s way. She knew what was a silly song and what was real.

The track finished. Next came the sequel song, ‘It’s Judy’s Turn to Cry’.

Listening as if for the first time to the ill-thought-of quickie follow-up record, Jordan realised it was a far deeper work. Lesley was reaching for a truth she could only flirt with in the original hit. Because Judy has left the party with Johnny, Lesley kisses ‘some other guy’, and when Johnny finds out, he hits him… because he still loves her. In the triumphalist gloat, Gore wasn’t the self-pitying reject of ‘It’s My Party’ but a teenage Medea, coldly joyful to have her feckless and violent boyfriend (‘he hit him’) back, but plotting revenge. Lesley would never forget being left for Judy. She had taken Johnny back because she could, and because Johnny was weak, a fool, a man. Later, she would make him pay.

There should be a third song, she realised, to complete the trilogy.

‘It’s My Baby, And I’ll Take It If I Want To.’

‘Johnny’s Turn to Die.’

‘Everybody Run, the Homecoming Queen’s Got a Gun.’ Instead, the next track was ‘You Don’t Own Me’.

She turned the CD off and stood in the dark, fire in her empty stomach, brain swarming.

She’d had it. She had tried, but it hadn’t worked out. No regrets. It had been a nice dream, but that’s all it was, a fairy story for children, like the Weezie books. Things weren’t different in the Hollow. She was still who she had been in the city. She had allowed herself to forget for a while, to be lulled into a party mood. She’d been giddy with fizz and wishes. Just another wrapping for desperation.

It wasn’t just Judy. Now, it was everybody’s turn to cry.

* * *

There had been an incursion in the night. Green Base was compromised, ivy curtains torn away and trampled, his reserves tampered with.

Tim nocked a pebble in the U-Dub and scanned the horizon. He detected no possible breach of the perimeter. He looked up at the house. The curtains in his parents�

�� room were still shut. It was well before breakfast hundred hours.

The BS’s curtains were open and she sat – asleep? – in her rocking chair, head hanging, nodding slightly. Tim took aim, in case the shape was a hostile in disguise. Over the sights of the U-Dub, he recognised her only too well.

Could it have been the IP?

So far, they’d been nothing but friendly. He had made no move to upset the balance, had always respected their need to stay in the shadows, had striven to watch out for their interests.

He looked back into the hollow tree.

There were scratches in the soft wood inside, like an animal might leave. But this was not the work of an animal. It had taken hands to wrench away the ivy.

Tim was alert, mind clear.

He needed to focus. It could be that the peace was ending.

All his life, he had strived to be ready for war. If this was it, he would not be caught by surprise. Mentally, he stepped up to DefCon 4. He would not attack unless directly threatened, but then he would respond with all he had, expecting no quarter and demanding no surrender. He would fight until the victory was won, and – if that were impossible – until there was no one left standing.

He took stock. Supplies would have to be replaced. There was no telling what had been done to them. They might have been turned against him.

He pulled back on the rubber of the U-Dub and did a slow three-sixty, hawkeye out for hostiles. His trained arm did not ache with the tension of holding the locked and loaded U-Dub. This might last a long time.

It wouldn’t be over by Christmas.

* * *

In the kitchen, Kirsty whisked. They had got into the habit of eating breakfast together. Today, only Steven came down in time. She was irritated to have broken too many eggs. Steven sat at the breakfast table, warming his neck in the early morning sun, reading the financial pages of the Independent.

It hit her how weird this was, like something from those hideous old films Jordan liked: housewifey slaving over cooked breakfast while hubby sits back and thinks money-making thoughts. She wasn’t supposed to bother her pretty little head with man’s business. Steven used to confide in her about deals he was putting together, soliciting her uninformed opinion. Understandably, that had changed. After Oddments, she was lucky not to be bankrupt. She could hardly expect to be treated as a financial consultant.

Still, when the Jordan thing was resolved, she’d broach the subject. With Tatum Hoyle – Tate ‘n’ Lyle, they called her – in the city, Steven needed things done here that Kirsty could manage easily. Her perfectly good degree (in journalism) had never really been put to use. She could at least type reports (word process, rather).

The Jordan thing, though.

She’d been whisking for several minutes. Butter sizzled brown in the pan. Concentrating, she scrambled eggs.

Tim wasn’t at the table, either. She’d heard him going out at some unholy hour.

She took two plates of scrambled egg on toast to the table and sat opposite Steven. The table caught the sun at just the right time.

He was absorbed in the paper.

‘Steven,’ she said.

‘Uh-huh.’ He didn’t look up.

‘About Jordan?’

He folded the paper with an almost subliminal sigh. A tiny thorn shifted in Kirsty’s chest. Her spine started to prickle. She had flashes of other mornings, sullen or shrieking. Behind her husband’s bland expression, she glimpsed the twisted, spittle-flecked mask his face had become during the worst of it.

‘She’s chucked, right?’ he asked.

She was guarded. ‘We don’t know that.’

‘Yes we do,’ he said kindly. ‘We knew Rick wouldn’t come, remember? You even said so once.’

‘That was before we moved, before everything changed.’

‘Rick didn’t move. So he didn’t change.’

That made sense. At least, it made Steven-sense. It was entirely inarguable, backed up with facts and figures and confirmed by rumours downloaded from a dozen Internet sites.

There was something she couldn’t trust about Steven-sense.

‘Would you call his father?’ she asked.

Steven performed a mock shudder, waving his knife and fork over his plate.

‘Could you imagine anything worse? What if your dad had called mine to ask about us?’

He was right. Probably.

‘It’s the uncertainty,’ she said.

‘What uncertainty?’

‘Aren’t you even concerned? Your daughter is upstairs crying her eyes out because of this bastard.’

‘That doesn’t sound like Jordan. You’re stereotyping.’

Kirsty remembered Jordan in her skeleton phase. She was stereotyping, she admitted, but only because she really didn’t want to think in personal, realistic terms about her daughter’s reaction to this soap-opera tragedy. She’d hoped all that was over with, left behind in London. Surely, it couldn’t happen again, not at the Hollow, not in the charmed place, not after the magic. Everything was changed.

‘Darling,’ Steven said, ‘Jordan’s too good for him, remember? Rick wasn’t as bad as all that, but he hardly had much in the way of gumption. She could run rings around him. She needs someone with more up top, more going for them. That’s always been her problem. She can’t find anyone to challenge her. When she’s bored, she turns in on herself, eats herself up from the inside.’

Who was good enough for Jordan? Kirsty had no answer. Did Steven? Or would no one ever be good enough for Daddy’s Little Darling?

Tim came in through the kitchen door, catapult in hand, as always.

‘Not at the table, Tim,’ she said.

Tim paused on the threshold, considered it, and slipped back outdoors, without a word.

Steven had the paper up again. Had he even looked at his son?

She had just eaten, scoffed down breakfast without tasting it, but felt empty, as if the two uneaten breakfasts fuelled her own burning hunger.

For the first time at the Hollow, she was frightened. She wanted to talk to Vron, but couldn’t. Her friend wasn’t at their café, a bus ride away, or prepared to make a house call. Vron was left behind, with all the bad things. There were no postcards with cryptic answers to questions only just forming in her mind. Kirsty hadn’t told Steven Vron had sent the books, had allowed him to give her credit for sleuthing them out on her own.

Vron was still out there, still in touch. That might be a lifeline soon.

Because things were going to have to change. Again.

Kirsty was not going to let herself be sucked into someone else’s dream. Support for her husband and concern for her kids were all very well, but what about her? Who supported and was concerned for her?

Steven hummed as he looked at the sports section. She understood she was on her own.

Very well. So be it. Watch out.

* * *

She rocked in her chair, not fast but evenly, foot up on the low window-sill. She left the photograph of Rick up on the mirror, preserving her room at a precise moment in history. From now on, she wouldn’t let anything change.

Jordan was inside herself, deep. She’d been here before. It was a comfort on some level, if only in the sense that she recognised the impossibility of comfort, the illusory nature of happiness.

It had all been a trick.

It wasn’t magic, it was conjuring.

She recognised she’d been rooked by Rick, by her parents, by the Hollow. She had been sold a lie, and now didn’t want to have the shreds of that lie clinging to her for the rest of her life.

She would devote herself to the cold, stark truth.

Behind her, the door opened a crack. She heard the small sound, as before. It wasn’t Mum. It was no one, just the Hollow.

‘Go away,’ she said firmly, not shouting, not whispering.

The door clicked shut.

‘Good,’ she said, settling that.

The family was wrong. As individua

ls, they were acceptable, even decent. Potentially good people. But they were mismatched. Like kippers and custard, Stravinsky and Sinatra. If ever a man and woman shouldn’t have married each other, it was Mum and Dad. If ever a marriage shouldn’t have had children, it was theirs. And if ever children could make a bad situation worse, they were Jordan and Tim. Each of the four was incompatible with the other three. Cross-currents of tension were doomed to grow and grow until there was an explosion. Yet, they stayed together. As a family, they were so inner-directed that splitting up, even for the sake of sanity, was never an option. You couldn’t divorce parents or children. If those ties remained, severing others wouldn’t make much difference.

It was a miracle Jordan wasn’t sucked into repeating the cycle with Rick. She saw how easily she could be turned into a replica of her mother, or even of her father, with mismatched kids of her own and future generations of misery in the offing.

Finally, when her knee began to scream, she stopped rocking. She had work to do.

She stripped off yesterday’s musty dress and stood in front of her mirror. Her coral knickers, the only underwear she’d been wearing, were the colour of her skin. Her tummy bulged over the elastic and her thighs were huge.

How had she let herself bloat like this?

It had been part of the trick, the cruellest trick.

She turned round, recognising a definite waddle, and looked over her shoulder at herself.

She was a pudgy monster. A disaster.

Everything swelled or sagged.

She didn’t let herself despair. She held her mind rigid. She’d have to set herself right. Her next project. She was alone in this, utterly.

She concealed her horrible body in an ugly dressing gown – one of Dad’s cast-offs – that hung to the floor and could be clutched around her chin, collar up to cover the furry beginnings of jowls.

Poking her head out of her room, she found the coast clear and darted across the corridor into the smaller bathroom. She locked the door behind her and let the blind fall with a rasping rattle.

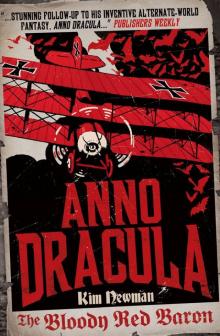

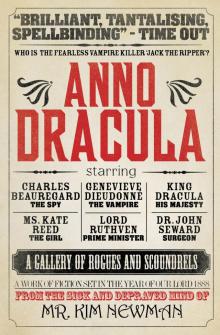

The Bloody Red Baron

The Bloody Red Baron Anno Dracula

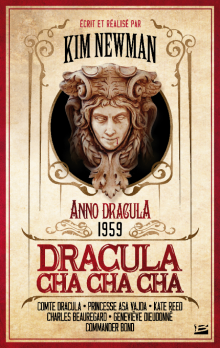

Anno Dracula Dracula Cha Cha Cha

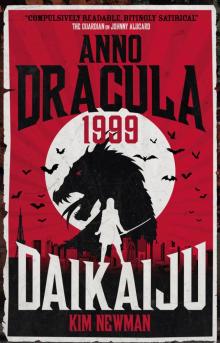

Dracula Cha Cha Cha Anno Dracula 1999

Anno Dracula 1999 Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles Angels of Music

Angels of Music The Man From the Diogenes Club

The Man From the Diogenes Club Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

Professor Moriarty: The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Night Mayor

The Night Mayor Back in the USSA

Back in the USSA Jago

Jago Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes

Gaslight Arcanum: Uncanny Tales of Sherlock Holmes The Quorum

The Quorum Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories

Anno Dracula 1899 and Other Stories Life's Lottery

Life's Lottery The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School

The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School Anno Dracula ad-1

Anno Dracula ad-1 The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2

The Bloody Red Baron: 1918 ad-2 An English Ghost Story

An English Ghost Story The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School

The Haunting of Drearcliff Grange School The Other Side of Midnight

The Other Side of Midnight Bad Dreams

Bad Dreams Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters

Anno Dracula--One Thousand Monsters The Hound Of The D’urbervilles

The Hound Of The D’urbervilles The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918

The Bloody Red Baron: Anno Dracula 1918